By Frank Matheis © 2017. Photos © Bill Steber

Meet Bill Steber, born in 1965, a true renaissance man, one of the finest artistic photographers of roots and blues music in the United States of America. If that sounds like a tall order, let’s add that he is also an amazing blues musician, who on the merit of that alone would deserve a flow of accolades.

The multi-talented artist resides in Murfeesboro, Tennessee, and is well known to readers of Living Blues magazine as a major contributor to the prestigious blues publication. As a documentarian of blues life, Bill Steber’s images are striking, intimate and powerful. Besides his technical proficiency, he manages to bring out the humanity of his photo subjects, in part because he is able to enter the milieu of the musicians, to enter their inner sanctums and capture them in a vulnerable, personal space. Steber exposes his musical subjects with an immediate privacy, an unprecedented closeness, as if you can see into their souls and feel their presence. His photography is not just high art, it’s brilliant existentialist expressionism of often romanticized perceptions, of lives, people and struggles that people imagine knowing something about, but can hardly understand. Steber’s masterful photos are revelatory of true blues culture. Yet, they do not demystify. Indeed, they expose how far separated most blues fans actually are with their over romanticized vision. People outside of the culture tend to create an illusion of what the blues world is, or what they think it should be, in their own imagination and image. His starkly expressive imagery confronts the viewer with the inner essence of the photo subject and at the same time, in a weird contradiction, imposes reality. This harsh confrontation with the delusion of our own lack of understanding at that moment reverts deserved dignity back to the subject. He strips it down to what is real. This is the power of documentary photography at its best.

His musicality is as impactful as his photography. He sings with a powerful blues voice, and he plays guitar and harmonica. Steber currently fronts the Hoodoo Men, a fierce, hard-driving, roots & blues, funky band with a Mississippi Hill Country vibe, that delves deep into the realms of the country blues. Their new album Goofer Dust, produced by Luther Dickinson, is an exploration of the mystical realm, of blues lore that is derived of West African ancient practices brought by slaves to America. The blues world draws may superstition and potions from these traditional African magical and religious rites. Steber sings and plays fiery versions of well-known traditionals, like Death Don’t Have No Mercy and Darling Corey. He enters the realm of dramatic expressionism, doing justice to Geeshie Wiley’s mournful Last Kind Word. The album closes with three Steber originals, aptly showcasing his songwriter prowess. His mark on the blues is made on multiple levels.

The countryblues.com caught up with the busy photographer bard and got him talking in an interview with Frank Matheis on October 22, 2017:

FM: When did you first start going down to Mississippi as a documentary photographer?

BS: That was exactly August of 1992. I had lived there as a child. I was born in Middle Tennessee, but when I was about a year old or less than a year old my family moved down to Forest, Mississippi for about a year, year and a half. My very earliest memories when I was two years old we were living in Mississippi. We lived down there for a while because of my dad’s work before we moved back. Mississippi, even as a child, was kind of a mythical place – sort of this fuzzy memories of my earliest infancy, childhood memories were of Mississippi.

FM: A lot of people take snapshots of musicians and they spend years doing it, but it never becomes more. But your work certainly transcends into the realm of really high quality artistic photography.

BS: Well, I appreciate that. That’s certainly my goal, I mean, the whole goal of all of it is that I want somebody to care about the image even if they don’t know who the person is or know any of the context or where it came from or like that. But if it has to stand up on its own, yet it’s even more an important goal for me that to be honest to the person and speak something about what their music sounds like, what the culture that they come from feels like, that in other words it’s an honest – it may be interpretive, and I do bring a lot of my own kind of interpretation to the work – obviously every photographer they say every picture you make is a self-portrait, whether you realize it or not, but to me I always want the pictures to at least feel like what the music sounds like.

FM: Let’s talk a little bit about how you started in your life. Where are you originally from?

BS: I grew up in a very small town in Middle Tennessee, called Centerville, Tennessee, and it’s the county seat of Hickman County. Hickman County is a very rural, pretty poor county in Middle Tennessee and it’s really almost like a little bit of Appalachia – even though it’s not connected to the Appalachian Mountains. It’s traditionally known for where Cousin Minnie Pearl is from – who was one of the first female stars of the Grand Ole Opry. Other than that, it’s mostly known for its moonshining because it was a very rural area with a lot of hills and hollers and places to hide. It was only 50 miles from Nashville with a lot of fresh water and caves and places to hide. With poverty in the South such as it was, and Prohibition lasting as long as it did, a lot of people made moonshine and sold it in Nashville, including some of my relatives. My mom always pointed out that half the family were preachers and the other half were moonshiners. I’m not so sure those didn’t overlap sometimes depending on the economy.

I grew up in a very rural area, pretty tight-knit community. It was steeped in the Southern music tradition. We listened to mostly traditional country, but I also discovered blues at a very early age, because my dad, who was in the Air Force, he bought records that were popular – the crossover artists that like teenagers in the South bought in the ‘50s were John Lee Hooker and Jimmy Reed. They were two of the biggest crossover artists of traditional blues. I discovered those at a very early age – just kind of blew my mind. It was different from anything else I ever heard. That started me on a lifelong love of really traditional blues.

FM: When did you start playing?

BS: It seems like I always played around ever since I can remember, since I was probably 10 – before 10 years old playing on my grandmother’s piano just hunt-and-peck single-finger picking out melodies. When I was about 11 or 12-years-old I got my first string-instrument. I got a dulcimer and learned a lot of the old traditional mountain tunes and things like that. But I didn’t really start seriously – I was out playing harmonica from high school on –took that up, got pretty decent at it. I didn’t take up guitar and other things until I got to college and at first played a lot of stuff that other people played – folk music – Bob Dylan and Neil Young and things like that. But eventually I worked my way back to the same passion that you have for country blues, and then later on picked up banjo, ukulele a little bit of mandolin, tenor banjo – all the stuff that I play in the Jake Leg Stompers. I played in bands on and off with friends all through my 20’s and 30’s, but I didn’t really get serious about it until I was almost 40 years old and we started the Jake Leg Stompers and really just started really, really working on repertoire, working on expanding the number of instruments I played and focusing in on what we wanted to say musically.

FM: What instruments do you play?

BS: I would say the primary three – harmonica, guitar and ukulele, specifically banjo ukulele. I really like to focus on the jug band /hokum tradition. A lot of the good-time music as far as public performance, because that music has always made me very, very happy – it’s very joyful music – a lot of the rags and various things that were popular in the late ‘20s, early ‘30s. Also because it was something that not many people in the Nashville area were doing – in fact, like almost nobody was doing this repertoire. So, we thought it would be something very fun. Nashville is just absolutely filled with great musicians. I mean some of the best musicians on each instrument in the world live in Nashville. So I thought, you know what? – I’m never going to compete for attention and gigs and things like that with those guys on a technical level, because those guys have been playing since they were children, and the best players in the world live here. But what I thought that was kind of maybe sorely lacking in the music scene here was bands that really brought back that joyful abandon that you find in so much of the first generation of recorded music from the’20s and ‘30s – you know, Memphis Jug Band and Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers and there were some phenomenal musicianship in those bands, but mostly what you got was this sense of just absolute joy that these people, when they were playing the music. And that’s really kind of the aesthetic that we kind of aspire to.

FM: Tell me a little bit about where you tour, where you regularly perform, and who else plays with you.

BS: Currently I have three different bands that I’m playing regularly. The main one is the Jake Leg Stompers. It’s a five-piece jug band/string band – and we mostly perform in the Nashville-Murfeesboro area and at festivals and special events in the Southeast, although we have played in Chicago and the Midwest and places like that.

Another band that most people haven’t heard of yet is – we’re just about to release our first album – is called the HooDoo Men, and that’s a two-man group with me and someone by the name of Sammy Baker who plays electric jug and drums. That music focuses on not only mostly prewar music, but a lot of the music by guys who were around in the prewar era but didn’t get to record until the ‘40s and ‘50s – you know, guys like Frankie Lee Sims and Lil’ Son Jackson and Lightnin’ Hopkins – those guys that still had that prewar acoustic sensibility but were some of the first guys to record electrically, sometimes on cheap equipment that gave a real kind of raw gritty juke joint sound – that’s kind of what we do with that band. And when I talk about the electric jug, what that does is he vocalizes the bass notes through a microphone. Originally we were using a headphone that we ran through – that we turned into a microphone. He runs that through a vocal processor that thickens it up and drops it an octave so you can get a really fat bass sound. So he can play the drums with feet and one hand, and then do all the bass notes vocalizing them like he would play the jug. And I play electrified harmonica and mostly acoustic guitars that are run through tubes to give a real kind of gritty sound. That’s been a really fun project that we’ve been doing.

And then the third group – I’ve been working for about a decade with Rambling Steve Gardner, who is originally from Pocahontas, Mississippi, but kind of holds down the traditional blues scene in Tokyo. And he comes back home to Mississippi once or twice a year and we tour around Mississippi and New Orleans and the South. But I’ve been to Japan with him three times, been to Germany and Austria, and then most recently we played the Maverick Festival in England and maybe very possibly going back there next year and doing a short tour of England. And I’ve also played just solo in Scotland – the Dundee Blues Festival there with my friend Alan Jones – if you don’t know him, he’s a really great player. And speaking of great players, the Jericho Road Show also consists of Wes Lee and Libby Rae Watson, two phenomenal solo artists in their own right. When the four of us get together, it’s really something special. I’m honored to play with those guys.”

FM: Let’s talk about how and when did photography come into the picture for you? Were you first a musician and then later started to photograph? When did the two merge together and create the scene that you have now, which is practicing musician and documentarian of music?

BS: I would say it all started from my love of music, which I’ve had since I can remember, just a deep need and love of music. The photography started when I was pretty young – 4th grade, 5th grade – you know, 10-, 11-, 12-years-old. My father was a serious amateur photographer. He put cameras in my hands at a very early age. Even in high school I worked for the high school newspaper and the yearbook; went to college, starting taking it serious, became a photo major –primarily interested in the artistic tradition rather than, say, not originally interested in documentary but just photography as a pure art form. Then I had to make some decisions about what am I going to do for a living – commercial work, work in studios or fashion? And I did that. I worked for some really great commercial photographers in Nashville, especially Russ Harrington who taught me everything I know about lighting. But I decided my really heart and soul I wanted to be a documentary photographer, a street photographer – but there’s no jobs for quote, “Street photography.” So I had to work my way into a job at the newspaper even though I never had an internship or taken a class in photojournalism. But early on in my career at the Tennessean (newspaper) I got a job within six months of graduating from college with a degree in English and photography. I worked my way onto the paper and I thought that would be the best way basically to learn how to do documentary work. Then within the first couple of years of – I guess about two and a half or three years in, I was sent on a trip to Mississippi with a writer, Joe Rogers, who was from Moss Point, Mississippi, to do a travel story. We went to the Natchez Trace and then came back up through the Delta, stopped at the home of Son Thomas. This was in August of 1992. When I walked into his little shotgun house there in Leland, the first thing I saw was he had one of the caskets with a sculpture of a dead woman laid in the casket, and one of his amazing clay sculptures of a skull up on a shelf with human teeth in them. I was just absolutely just thunderstruck by the power of this imagery. And then Pat – his son – took me to the back bedroom and we hung out for a while and I played a little bit of music with him and made a few pictures of him. I was just electrified. This first trip to the Delta, it changed my life. I was like, I have to get back here as soon as possible – without any kind of grand scheme – I just physically have to be here.

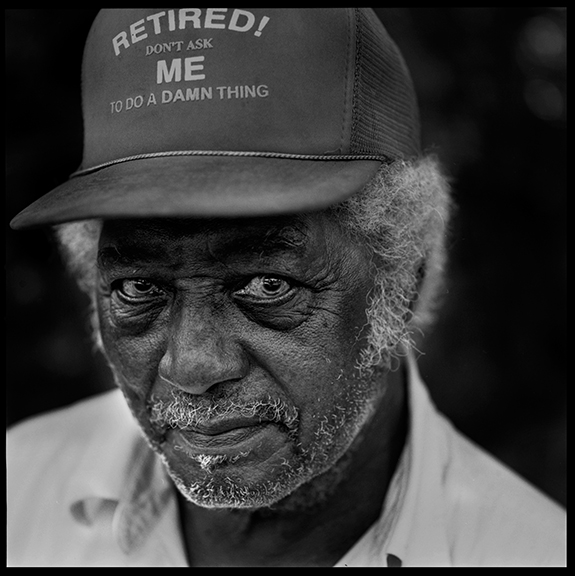

![A former grave digger and day laborer, James "Sonny Ford" Thomas became internationally known as much for his highly evocative folk art of skulls, corpses and animals as for his talents as a blues artist. In song, Thomas often celebrated "61 Hwy" which runs from Chicago to New Orleans, passing a few hundred feet from the front door of his modest shotgun shack in Leland, MS . Of Thomas' music, William Ferris wrote in his 1978 book Blues From The Delta: "Rural blues men like [Thomas] describe isolation with stark images like an empty room or a highway in the Mississipi countryside." Thomas was known for his wavering, falsetto voice with which he sang songs like, "I'm sitting here a thousand miles from nowhere in this one room country shack/ I wake up every night about midnight, I just can't sleep/ All the crickets keep me company, you know the wind howling round my feet/ Rocks is my pillow and cold ground is my bed/ The highway is my home/ Lord I might as well be dead."](https://www.thecountryblues.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Son-Thomas-1.jpg)

By the next spring – in May actually went down for a blues festival in Greenwood – I was going to go see Son again – he was already back in the hospital – he died in June of that year. I had this urgency fall on me, like my God, I just now found this person that has just changed my life and within a few months he’s already gone. And I said what else is here that’s disappearing? So I had this fire lit under me to – I’m working a full-time, you know 50 hours a week, at the newspaper. But every time I would have a long weekend or take some vacation time, get four or five days off so that the next several years I just spent all of my time, all of my extra time I could make, driving down to Mississippi, expanding my knowledge base of what’s important to photograph. Then it moved on to the fife and drum music. I got interested in religion, looking for people who still hand-picked cotton – any kind of the traditions that feed into the blues, that are the cultural context of the blues. Not just – you know, pretty early on I kind of got bored with the stereotypes of the older black man sitting on his porch playing guitar. I mean that’s the stereotype. I wanted to go deeper. You know, what cultural forces informed the creation of the culture that gave rise to the blues? What remnants of that culture are still left? So I really got fascinated in specifically hoodoo practices and folk superstitions that can be traced back to West Africa. You know, like bottle trees and encircling charms around trees in the yard, and ghost mirrors, using an axe to split a storm, hanging dimes around the ankle – silver dimes – to see if someone has goofer-dusted up your path. And the more I learned the more I realized I had – there was more to learn. So it was just steamrolled from there. And I still go and I still am collecting as much as I can.

The trajectory of that has obviously slowed after 25 years, because almost all the original folks that I met have died off. But there’s so many traditions in some of the areas that are still much of the hill country — still very vibrant. You know, the sons, daughters —

FM: A the present time are you still engaged as at the newspaper ?

BS: I left my newspaper job in 2004 and have mostly just done freelance photography work and then music. I didn’t really start getting serious about music until right after I left because I had this long-time plan to have a jug band or some sort of really fun traditional musical outfit. But it was impossible to do while I had a full-time job at the newspaper and trying to do all this documentary work, and supplement my income with freelance work. It was only after leaving the newspaper that I had the time to start pursuing music. In the beginning, of course pursuing the music was not really seen as a profession but just something to feed my soul, just something I had to do. It was really Steve Gardner who gave me a lot of the encouragement and permission – because I was like so many people, I just loved these Southern traditions. Even though I’m from the South, it was of a generation, and much of the music comes from that tradition of Mississippi and West Tennessee. It took me a long time to give myself kind of permission to play the music. Once we started playing out in public I realized that, well you know, I could have my own voice within the tradition and use – my goal early on, and to this day, is still basically advocacy for the culture. So everything I do with the photography is about saying, “Look at this amazing culture.” Pay attention to it. Nurture it. Support it. And what we’ve done with the music is exactly the same. I’ve been accused of being too verbal in shows because I’ll tell the history behind the songs, say why it’s important, encourage people to go seek out the original traditional musical. But I also feel it’s a duty and really kind of my mission in life. It’s not about me. It’s not about saying, like, Listen to me. It’s about saying that I’m the person that has your attention right now and it’s our duty to really render this tradition with as much of not only ability but with as much enthusiasm and fun and passion so that somebody will listen to it and go, like, “My gosh, I didn’t” – I’ve had people come up to me after a show and say, “You know, I don’t think I really know any of the songs you just played, but I feel like I knew all of them” – because it taps into the DNA of American culture. Everything comes out of this tradition. So if I can get some people passionate about it, either through photography or through the music, to seek out the original practitioners on their own, then I’ve done my job.

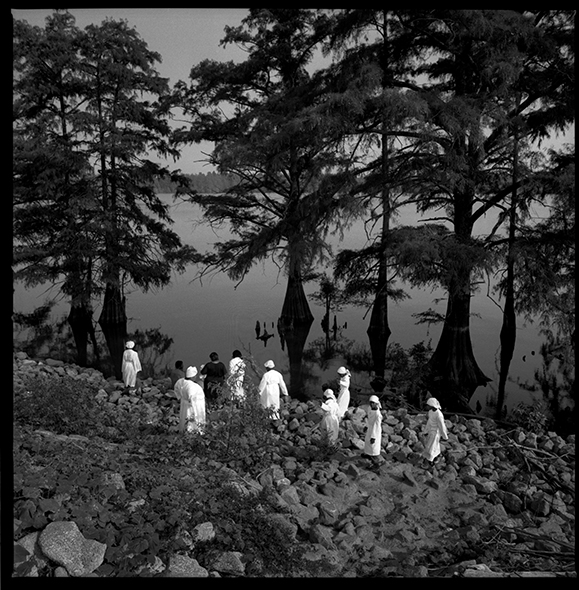

A group of baptism candidates make their way carefully over loose stones to the edge of Moon Lake, an oxbow of the Mississippi near Lula, MS.

One of the things that I’m fortunate enough to do is that I’ve been working with Living Blues since the ‘90s. And usually once a year they do a themed issue, and more often than not Scott Barretta and I – like I do most of the photography and he and Jim O’Neal do much of the writing. For this past year it was the Yazoo County issue. I did almost all the photographs for that – contemporary photographs. And also it gives me an opportunity to go deep in my archives and for all the Bentonia stuff I’ve had with Jack Owens, all the pictures – I’ve been photographing Jimmy Duck Holmes for 20-some-odd years, and documenting the scene at the Blue Front. It’s a wonderful opportunity for me to dig in the archives and show some of the moments I’ve been honored to witness. We’ve done whole issues on Chicago, New Orleans, and back in Mississippi and the Blues Trail. So every year I usually get to do almost an entire issue.

FM: You said you’re just about to release a CD?

BS: Yes. That’s Hoodoo Men, and the record is called Goofer Dust. And it has some original songs on there, but much of it, like I said – we’ve got – the lead track is by Big Lucky Carter, Levester Big Lucky Carter. His song Goofer Dust – and the reason I love that song – I guess the energy in about the song. It was one of the only songs in the blues tradition that specifically outlined hoodoo practices and potions and spells, things like that. A lot of times, you know, Hoochy Coochy Man and different ones for use of hoodoo is often used as a metaphor for revenge or sexual prowess or something like that. And it hasn’t been a long tradition of them talking about hoodoo as a spiritual practice. This one, it also follows that tradition of saying the woman has done hoodoos –sprinkles goofer dust and all that. But it really specifically gets into details. And I went with him, Big Lucky Carter, back in the’90s over to Schwab’s in Memphis, which is one of the only real botanicas for hoodoo stuff there left in the South, and interviewed him extensively about the songs so – we musically changed it but kept his lyrics. And that’s the idea kind of behind the Hoodoo Men, is kind of draw forth on that amazing Southern tradition of hoodoo. The official release date is November 4th 2017, and it will be the first thing I’ve ever done on vinyl. We have a CD version and 12-inch vinyl.