By Frank Matheis

“…go on with your bad self and let it out – sing louder and be more adventurous”

You are going to love her!

Albanie Falletta is an exquisite and fierce roots, blues, jazz, ragtime and swing guitarist extraordinaire, and a superb singer, one of the main ascending women in the blues today. She is passionate, exciting and virtuosic, simply thrilling. These descriptions all fit, and she represents an amalgam that connects all of these musical forms together: “My whole philosophy about music comes down to connections and inter-connectedness of people and musical styles. I think the inclination to gentrefy music, to create a lot of divisiveness and limit it to “either that or this” is not for me. I really believe that all music is connected, especially in my studies of turn of the century music. I really believe that all people are connected –to our history and our family path and collective history with humans – which is one of the reasons I feel I really connected to the blues as a kid, as a young white girl who grew up in Louisiana and Texas. I was able to tap into that – the emotion of the blues – the playfulness of it, the sadness of it. I can’t really explain that. You can’t really put that in a box. I just hope that I’m, as an artist, continuing to stay open to new ideas and to new inputs and philosophies and possible connections between things and never really stay in one place. I have no desire to be known as a blues guitarist or a jazz guitarist or a singer/songwriter. I definitely love these songsters, who encompass all of those things, and artists representing music that is played for the enjoyment of the people and the spirit of the people. I really think music should serve the people and keep us feeling interconnected instead of divided.”

She also does not emphasize her role as a woman in the blues. During the interview, she was intrigued by a question that did not get asked: “Well, I’m surprised you didn’t ask about being a woman – but I’m also kind of relieved. That seems to be a thing that people focus on so much, because there are so few of us – I mean these days maybe not so much. I certainly have a lot of friends who are female – women that play music and plays the blues. So I’m actually glad you didn’t decide to make a big deal of that, because I certainly don’t… I think that’s one of the biggest issues we have – young girls don’t grow up with a role model – like if they don’t see that there are women out there playing the blues and playing guitar and playing really proficiently, then they don’t have a reference point that – oh, I can do this thing too.”

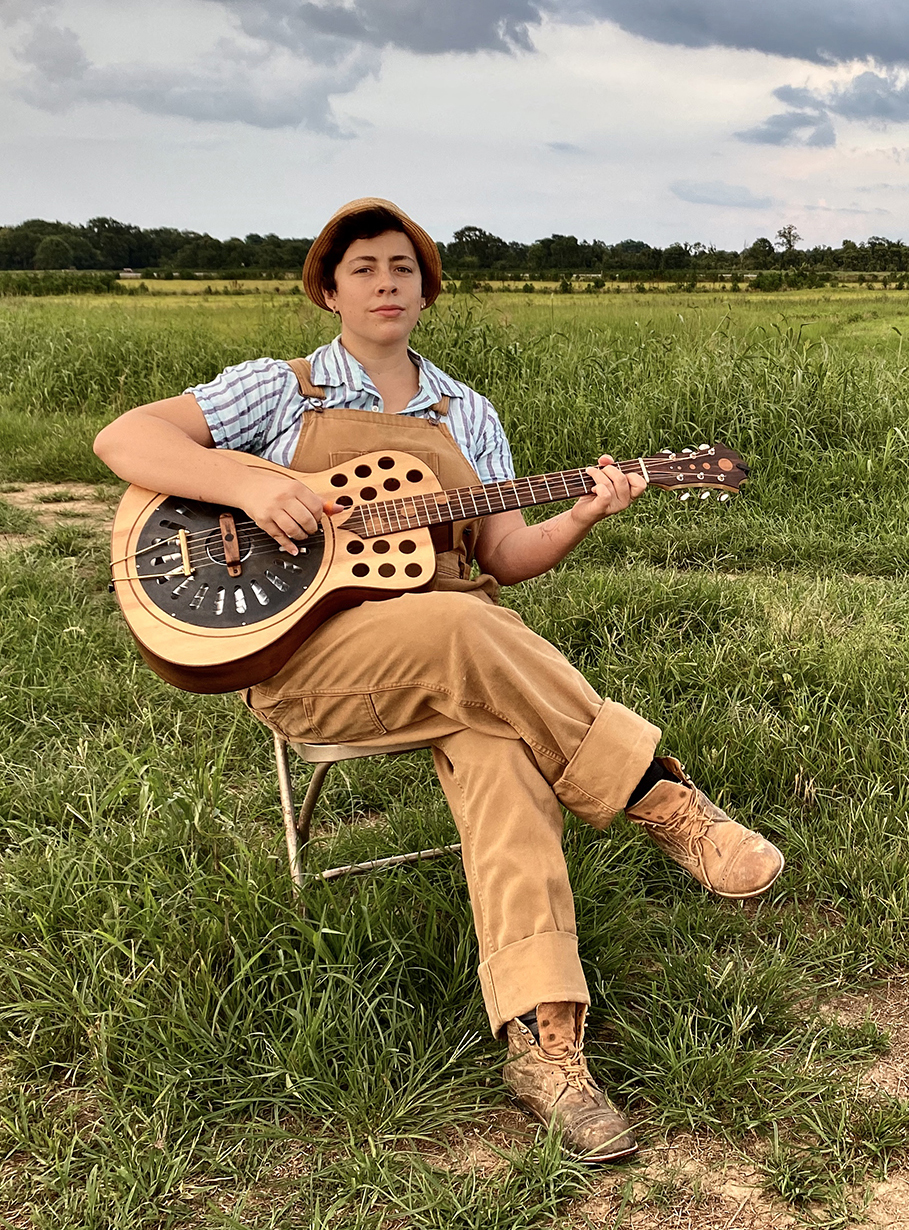

The immensely talented chanteuse, with the coolest style and expressive individualism, comes from Monroe in North Louisiana and now makes her home in Flatbush, Brooklyn, by way of New Orleans. Her family is Cajun and the other half Sicilian. Albanie is a Cajun name, the name of her great-great-grandmother. When she lets loose on her custom-made Ben Bonham resonator guitar eyes light up with delight. She can swing, and how!

and thecountryblues.com caught up with the amazing bard on May 3, 2020 during the pandemic lockdown as she escaped the city to Eunice, Louisiana, in what she called “a country bunker:”

AF: “I definitely didn’t grow up in blues culture necessarily. I remember really connecting with the performers who played at the local folklife festival and I think I was such an angsty kid so the music just really spoke to me. I just have always loved acoustic music. It just feels so real. It feels so salt of the earth. You can hear the vibrations bouncing off the wall, and that’s a natural thing instead of having this high-volume noise coming at you either against or with your consent. So that was it. I was just drawn to the folk music aspect of it and the storytelling music aspect and just the expression of the human condition. There are things in life that we don’t always get to take part of and just that sense of kind of longing for something. I just always was fascinated with that aspect of human expression…

I came to the music I play now through a lot of different paths. Blues was definitely my first love. As a kid, growing up in Louisiana, I got to hear a lot of live blues at the Louisiana Folklife Festival in Monroe. My family and I relocated to Texas when I was nine – near Austin. When I was around age 10, my uncle gave me John Lee Hooker album, and he started feeding me Son House and Lightnin’ Hopkins records, and I got super into that. I went through my punk rock/hair metal phase. Then got into Django Reinhardt in my first year of high school. I happened to go to this really cool creative arts high school in Wimberley, Texas, called KAPS– that had a guitar class, and the guitar teacher, Django Porter, happened to be named Django by his father and also specialized in the Manouche style [Gypsy] swing. I got really into that for the majority of my high school time and was playing that in and around Austin with different bands and my teacher. Then I started studying under a guy named Slim Richey, who just passed away a couple of years ago. He was an awesome legend – very Gandalf looking swing guitar player, and he was more into early American swing and more into like later styles like Wes Montgomery. He turned me on to Charlie Christian and Eddie Durham, who also grew up in the town we lived in, San Marcos, Texas. I got into more electric style swing and then I got back into the blues, because I moved into a house in South Austin – I guess I was about 23, I happened to be neighbors with Guy Forsyth, who is a great Austin blues guitarist and singer and songwriter. We ended up playing tunes. He was in the process of reviving his band, called the Hot Nut Riveters –a spin off of the Asylum Street Spankers, which he helped to found. We were playing some blues and some Baudeville, Hokum ‘20s music with inappropriate themes. He introduced me to Steve James, and I ended up going to a concert that Steve played in a local music shop. I just really fell in love with his playing and his knowledge of the history of blues music. That was right before I moved to New Orleans. I took lessons with Steve, and he showed me how to fingerpick – very slowly, methodically and patiently. I’m not sure how he has that much patience. It took me a really long time – maybe seven months before I could really do it. That became a part of my regular thing. I’d drive to Austin and study with Steve and pick up more knowledge and learn about more people to listen to.

We had been on a tour up to the Kansas City Folk Alliance. Mark Rubin was running the music teaching part of it, so he had our whole band teaching lessons. Somehow, we got in on that, teaching during the day and that’s how I met the California Feetwarmers and Jerron Paxton, and got kind of turned on to this whole world of ragtime in conjunction with blues. I’ve been forever corrupted by the world of ragtime.

I met Phil Wiggins met at Centrum in Port Townsend, Washington. I met a lot of the blues folks that do Augusta and Centrum and I ended up getting asked to teach swing guitar at Augusta, where I got to spend a lot of time listening to Phil and playing some with him in the wee hours – so many magical moments at Augusta last year and I’m very sad we won’t be able to congregate this time around.?

At the Weiser Fiddle Contest and Festival in Idaho, which is a lovely, lovely camp , a community gathering place for folks to show up to sit in a desert field and play music for hours on end. There I met Ben Bonham and he had these homemade guitars he was trying to hawk to the people at the festival. He had really just started building guitars the year I met him. That was about six years ago. Maybe my timeline is off, but anyway, several years ago. I kind of jokingly was playing one of his guitars and fell in love with it, and I just said, “Can I have this?” And he said, “No way in hell you can have that.” You know, he was not pleased with my joke. So eventually I did buy one of his guitars at Weiser, and loved it. Then I realized the neck was not wide enough for finger-picking and so he said, “Well, do you want a custom one? Send in your measurements and we’ll trade them in, or you can sell that one and pay me back.” So, I did. He put these beautiful moons across the fretboard and really made it a work of art. It’s loud and I love it.”

Slightly out of chronological order, her experience in New Orleans makes for poignant insights to close the interview:

“In July 2013, I moved to New Orleans. I always wanted to live there since I was a kid – it’s kind of a mystical place for me, after hearing so much music that came out of there. When I turned 20, I really got into Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet and Bix Beiderbecke and some of that early ‘20s jazz. Things in Austin had shifted for me and I just decided to move there. I didn’t really have any plans. I met several of the musicians down there, but was a pilgrimage. I really wanted to move to New Orleans to play traditional jazz and to play it with people who grew up in that tradition. I lived there for six and a half years and just gained so much. It was a hard – as the music business goes. It’s hard to make a living, but I definitely did that at times, and most importantly, I got to connect with some of the New Orleans music elders who are part of the lineage of the folks that this music was invented by. I got to spend a lot of time with Wendell Brunious, whose father and several of his family members played at Preservation Hall and led the Preservation Hall Jazz Band. He led the Preservation Hall Jazz Band for 20 years or more. Speaking with Wendell or being near him felt like the magic. The spirit of the city of New Orleans kind of rubs off on you – effortlessly, because that man really embodies the spirit of New Orleans and the spirit of that music. I feel like what I really needed to learn from New Orleans is that thing that all music is folk music. Not any Joe Schmo can play the jazz. But folks like Wendell and some of the elders who play at the Hall really included me in a way that I had not felt before – as if I were a family member. They saw that I was eager to play and learn, and they just would encourage me to sit in with them, be on stage with them, be in the tribe. It took me a while to get used to it, but I would sing something that Wendell liked or someone liked, and they’d shout at me – it used to terrify me – I thought I was doing something wrong, but really it was just like go on with your bad self and let it out – sing louder and be more adventurous. I really felt I was taken in and taught how to create music within a community context. This music is our lifeblood it’s just part of who we are and what we do. And just like how in New Orleans the grieving process is a public experience – people take it to the streets. You’re in the tribe when Fats Domino dies and you’re marching down the street and dancing and processing the grief in this like community sense . It taught me so much and it was so healing in this world of – we’re separated — we’re all just sitting behind our computer screens, talking to each other but not actually physically, spiritually interacting. I learned so much about music in those years. I continue to learn from those people.”

Definitely skip past the commercials on this blues: