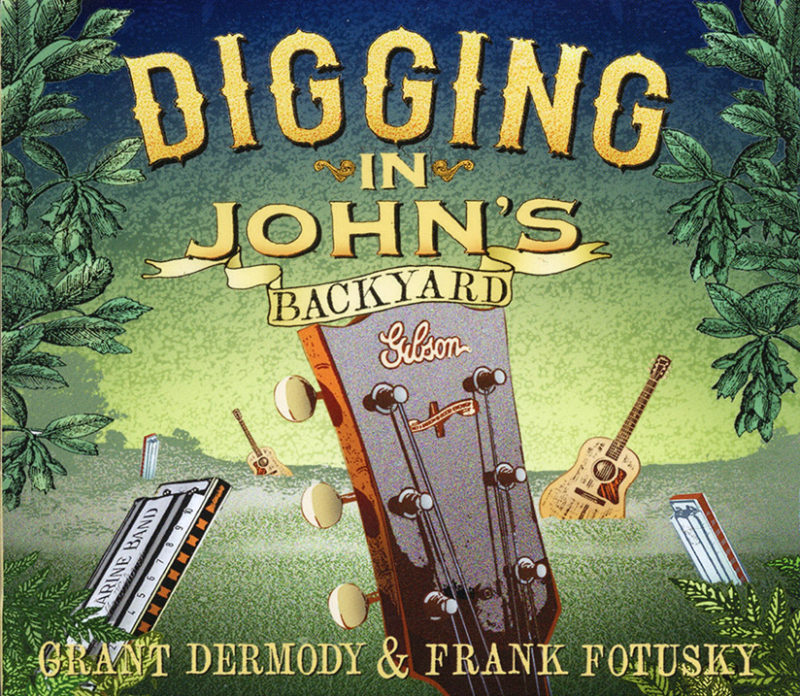

Digging in John’s Backyard, Self-Produced 2022

Readers are encouraged to read the extensive features of both Frank Fotusky and Grant Dermody on this site.

Here we have a new tribute to the great Piedmont blues picker John Jackson by two of today’s finest practitioners of the acoustic, fingerpicking East Coast blues sub-genre. It’s seldom when the musicians and the CD reviewer have something unifying in common before the writing process even starts – here, all three loved John Jackson. Harmonica ace Grant Dermody and virtuoso guitarist Frank Fotusky were longtime friends of John Jackson, who mentored both musically. This writer can’t make the claim of mentorship, but Frank Matheis was also friendly with Jackson, with whom he had numerous enjoyable times together. Indeed, this blues website is dedicated to John Jackson.

John Jackson – one of the finest Piedmont Pickers

Just about everyone who ever had the pleasure of knowing John Jackson will attest that he was one of the kindest, sweetest and most wonderful people they had ever met in their lifetimes. The mild mannered, good natured Virginia native was an important and much beloved member of the D.C. blues scene. John Jackson was an exquisite instrumentalist and versatile musician who mastered complex fingerpicking and a wide repertoire of music on guitar, banjo and harmonica. He was a true cultural treasure of American roots music. Like his friend John Cephas, Jackson was awarded the National Heritage “Living Treasure” fellowship from the National Endowment of the Arts in 1986, a huge honor for a brilliant musician whose life was filled with hardship and sorrow, but who internalized it through personal kindness and musical expression.

John Jackson was born in Woodville, in Rappahannock County on the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, on February 25, 1924. He always appeared neat and debonair, in his trademark fedora hat and a bola tie, like a country gentleman. He never took the stage without a sports coat, even during hot summer shows, looking good as the best-dressed man at the concert. Perhaps because for most of his life he wore work clothes, first as a poor kid raised on the Virginia mountain farm as the seventh of 14 children, then as chauffeur, butler and gravedigger. He only had a few years of education and was unable to read and write as he had to start working as a child. He knew countless songs, and even short conversations with him revealed knowledge of a vast musical repertoire, possibly hundreds of songs. His was a carrier of oral history, a large body of knowledge that he retained over a lifetime. He had the memory of an elephant and was a remarkable storyteller, a witty man with a wry country humor who recollected details and names with fascinating sharpness. His brain was able to compensate for his inability to read and write by developing ways to use his mind in other ways, as a walking songbook of American roots music – all from memory. In order to imprint hundreds of song lyrics, the music and melody to memory, the brain must be trained to quickly absorb and retain information, which requires almost superhuman concentration. This manifested itself in everything he did, including when he toiled as a gravedigger. The people who knew him attested that when he dug a grave, it was a spiritual process. He saw the act of digging the grave as God’s work that he had to perform with absolute perfection, in an almost Zen like focus. His manager Patricia Byerly recalled, “He had the ability to focus on things that was extraordinary. He talked about digging graves, and how people would laugh at him because he was a gravedigger. He’d say, but not in front of them, he would say, “That’s okay, it doesn’t matter what they say. Laying people to their final resting place is God’s work and not everyone can do it. You have to be called for it.” When he was digging a grave, he was always very respectful. He concentrated with total focus and made the grave perfectly symmetrical, with clean lines and corners. He concentrated with such intensity until it was immaculate. That’s why they asked him to dig Robert Kennedy’s grave. So that was one of the things that made him extraordinary.”

Jackson spoke plainly and simply with a thick regional dialect. His beautifully melodic native speech would be worth a philologist’s study, as Jackson had a tendency insert extra vowels into words, creating a lilting downward glide of the letter, followed by a sudden raising, not unlike the blue note. He pronounced “bad” as “ba-ye-ad” and “am” and “a-ye-m”, “door” as “doo-ah.” Apparently the black community in Rappahannock County had developed unique linguistic elements, virtually a pocket of a distinct dialect, because of the segregation and isolation of that community since slavery days. When John Jackson moved to Fairfax, Virginia in 1949, even the other black folks were unfamiliar with his rare East Virginia dialect that was a “singing way of talking.” His actual singing had a warm tone, ethereal and gritty with a real twang. Combined with his unique dialect, his singing was both idiosyncratic and compelling.

John Jackson’s music incorporated everything from blues to hillbilly. Today is often classified as a Piedmont blues player, but one could equally define him as a songster, a black Appalachian musician, perhaps most comparable to his contemporary Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson, the blind white North Carolina bard. Both Watson and Jackson were rural east coast musicians who played a bit of everything that they heard in Appalachia, the Piedmont and Tidewater region of the mid-Atlantic states, be it blues, country, bluegrass or pre-bluegrass mountain music, gospel, folk and just about any other category. Both of them were equally well versed on banjo and guitar, and both had mastered a wide range of styles, and they played many of the same songs in their respective repertoire, regional favorites popular with white and black audiences. To these musicians, each remarkable instrumentalists, external categorization and classification was irrelevant. John Jackson told Frank Matheis in 1987, “We played blues and mostly we just liked songs. If we heard a song, on the radio or on the record, and if we liked it, we played that song. We didn’t call it anything except a song and the name of the song. My favorite was Jimmie Rodgers. I liked just about everything he sang and so did we all. I learned a lot of his songs and I loved to play them still. I also played blues from the records and learned all those songs. We played everything if we liked it.”

Writers always asked Jackson who had been his biggest influence, and notably, he virtually always mentioned Jimmie Rodgers first, the “yodeling brakeman” from Terre, Mississippi, a white country singer who had been profoundly influenced by the black blues. In fact, Jimmie Rodgers was very popular among the African American community. John Cephahs and Archie Edwards also liked his music a great deal. Country music generally was much more popular than generally accepted, including the radio show coming from the Grand Ol’ Opry

Phil Wiggins said, “John Jackson went through some hard times in his life, some really serious stuff. Yet, he didn’t let it get to him. He always had a sunny disposition and he was just the sweetest, nicest man there ever was. Other people who complain so loudly didn’t go through half of what he went through and they are bitter and angry at everyone and the world. Not John Jackson. He was just a sweetheart of a man who never let anything affect his good nature.”

One of John Jackson’s favorite hobbies was digging for and collecting Civil War artifacts, which were widely found in his home area which is riddled with Civil War battlefields. Thus, the fitting album title Digging in John’s Backyard. He dug graves for a living and artifacts for fun.

A refined blues duo pays a fitting tribute

Frank Fotusky and Grant Dermody are both among the preeminent practitioners of the country blues today, superb instrumentalists respectively. This project had special personal meaning to them and they created this tribute not by attempting the impossible task of mimicking Jackson. Frank Fotusky said, “We chose a few that were among John’s favorites, his most known original and others that would honor him and reflect the deep tradition of the genre. Hence the title of the album.”

In the end effect, people might not know John Jackson when listening to this elegant new album by the acoustic duo. The album has to stand on its own and thankfully it is a refined and excellent record, played superbly and passionately. Frank Fotusky is one of the finest fingerpickers on the acoustic music scene, be it blues or other roots music. His singing range is remarkably close to Jorma Kaukonen, and he has mastered the alternating bass fingerpicking style exquisitely. Grant Dermody is a sensitive harmonica player who plays tastefully and sweetly. Together they are a perfectly matched duo and their album will bring a smile to any blues fan.

The album packs 13 consistently even songs. Noticeably, there is also a tip of the hat to John Jackson’s friend John Cephas. The duo covers his song Seattle Rainy Day Blues and the Skip James song Hard Time Killing Floor, which John Cephas played as part of his regular repertoire. The closest song in Jackson’s style is his song Boats Up River, with both musicians singing. Their cover of another Piedmont picker’s song Death Don’t Have No Mercy would have brought a smile to the influential Rev. Gary Davis. They bring on the lovely rarity Gonna Lay Down My Old Guitar by Alton Delmore. Both show off their skills on Blind Blake’s famous Police Dog Blues.

Altogether, Digging in John’s Backyard is a keeper, a must for any blues fan’s collection, a wonderful tribute to John Jackson. A writer could line up a long list of fitting adjectives to describe this lovely, sweet album. Perhaps the best compliment would be to say, “John Jackson would have loved it.” This writer surely did.