By Frank Matheis

By Frank Matheis

This is the full, unedited version of the essay ‘John Hurt’ by Frank Matheis, as published in the book ‘Sweet Bitter Blues – Washington’s Homemade Blues’ by Phil Wiggins and Frank Matheis. University Press of Mississippi, 2020.

The popular blues press of the time referred to him by his marketing stage name as “Mississippi” John Hurt, but in Archie’s barbershop on 2007 Bunker Hill Rd. NE he was simply called “John.” For the years 1963-1966 that Hurt lived in D.C. with his wife Jessie and two grandchildren, he was in two worlds– in his new career in the white music establishment, with his handlers and managers; and, his private life in the black community where he could feel at “home”[1] and where he had a special friend, Archie Edwards, and many more, including Philadelphia Jerry Ricks who often visited Washington, D.C. Hurt used to get his hair cut at Archie Edwards’ barbershop, and he and Archie often played together at the barbershop’s famed jam sessions. Archie was his friend and musical kin whom he referred to as “Brother Arch.” The relationship between Edwards and Hurt would be one of the building blocks of the blues scene in Archie’s barbershop, the center of the D.C. acoustic blues scene, and impact the region’s music for decades to come.

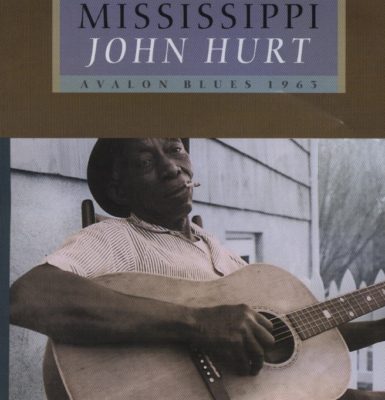

Hurt, from Avalon, Mississippi, was one of the great “rediscovered” artists of the golden era of country blues and one of the most beloved figures in folk music. His music is so accessible that even people who claim not to like the blues have an affinity for this bluesman and songster. Perhaps it was because of his melodically elegant and subtle style, his lilting, wistful music that touches people’s hearts with his syncopated, refined and intricate alternating bass fingerpicking style, with fluid left hand arpeggios – a similar style to the east Coast fingerpicking often called Piedmont blues. He played with a light beat and a gentle sweetness – accompanied by his soothing voice. You could feel the love in his music and he was often described as an affable, kind, sweet, unassuming old man, always in a worn old felt fedora hat. He played with a smile and put a smile on those fortunate enough to have heard him play in his lifetime. He may have been diminutive in size, but he remains an adored giant of folk music to this day. According to photographer and folk music manager Dick Waterman, John Hurt once told him his biggest wish in the whole wide world: “If I was to have just one wish and I knew that wish was to come true, I would wish…I would wish that everyone in this world would love me just like I love everyone in the world.”[2] Surely that wish has come true. Now, five decades after his death, he remains one of the most beloved figures in folk music.

John Smith Hurt was born in 1892 in Teoc, Mississippi, in the hill country of the Delta region, and was raised in nearby Avalon, a small rural community. He only had four years of formal education and worked as a sharecropper and was a self-taught guitarist. As published in the liner notes of the 1997 Rounder record Mississippi John Hurt- Legend, John Hurt in 1963 said,

“I learned to play guitar at age of nine. A week after that my mother bought me a second-hand guitar at the price of $1.50. No guitar has no more beautifuler sound. At age of 14, I went to playing for country dances. Also, private homes. At this time, I was working very hard on a farm near Avalon, Mississippi. In the years of ‘28 and ‘29, I recorded for the Okeh Recording Company at Memphis, Tennessee, in ‘28, in New York in ’29.[3] After that I came back to my home in Mississippi. Worked hard on a farm for my living. Worked on the river with the U.S. Engineers, also work some on the railroad and on W.P.A. project. Now I’m on the road again with the Piedmont Record Company.”

In an often-told story, he was long forgotten, perhaps assumed deceased, faded into musical obscurity, the way of many of the musicians who recorded sides for the “race records” of the 1920s and 30s. Most were paid a pittance in the early days to record 78-rpm sides that were sold to the African American blues audience. There was no mass appeal for these rural blues records in the jazz era and most were released regionally in small quantity pressings.

In 1963, a member of the so-called “Blues Mafia” of Washington, D.C., Tom Hoskins, aka “Fang,” was turned on to two tracks on the Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music by blues collector, musicologist and radio personality Dick Spottswood. The “Blues Mafia” were mostly white college students in the Maryland, Washington, D.C., Virginia tristate area, collectors of old 78-rpm records, musicians and early blues fans. Hoskins picked up on Hurt’s now famous song lyric Avalon Blues: “Avalon’s my hometown, always on my mind/ Pretty mamas in Avalon, want me there all the time.” He subsequently traveled to Avalon, Mississippi and reported finding the old singer “working cattle on a farm” and living in a shack along a dirt road in relative poverty, not an unusual scenario for rural African Americans in the Deep South during the Jim Crow segregation era. He often described that Hurt did not even own a guitar.[4]

Hoskins brought Hurt to D.C. to launch his new career, and for all practical purposes it was a success. Hurt, by then just over 70 years old but still musically skilled, played the Newport Folk Festival and the Philadelphia Folk Festival. He actively toured the college and coffeehouse concert circuit. He was a guest on the biggest TV talk show of the time, Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, featured in Newsweek, Down Beat, Time, and the New York Times, and celebrated as the “Dramatic rediscovery of a near legendary musician.” Young white kids flocked to his shows and concerts. Many articles were written. Vanguard Records issued a series of albums. His songs were also recorded for the Library of Congress and included in countless compilations. The 1928 Okeh recordings were reissued. Yet, he returned to Mississippi in 1966, only a few short years after being rediscovered, where he soon after died of a heart attack.[5] He did not have much to show for the three years of fame.

Photographer and music manager Dick Waterman acknowledged, “John never felt at home in white society and every time that we drove into a new city, he would anxiously scan the streets to find ‘someone that looks like me.’”[6] In Hurt’s D.C. years, there were places where he could go and simply feel at home, with people who did not have ulterior motives, where he was not a novelty and where he did not have to be anyone other than himself. One of those places was Archie’s barbershop and one of those people was Archie Edwards.

In 1978, German record producer and photographer Axel Küstner interviewed Archie, who spoke of John Hurt:[7]

“I used to do a lot of his stuff. Mississippi John Hurt – I worked with him in person, here in Washington. He lived here for about three years, and I met him when he was performing down at the Ontario Place (a coffee house) in Washington, D.C. Since I had learned some of his music when I was a kid, we just started playing together. His Stack-O-Lee and Candy Man Blues I learned when I was a kid. But what made me so interested in him was that after 35 years after learning some of his music, I met him. Then we worked together for three years and he went back to Mississippi and passed away. The last three years of his lifetime I was his buddy. I learned quite a few of his songs during the time that he and I worked together. He asked me to learn them and teach them to other people. He asked me not to let his music die, you know. Said if I could learn it and could pass it on to someone else he would still be alive. It was quite a coincidence about me being a country blues musician who had admired him all this long time and getting a chance to meet him. It was quite a story, but I guess it was something that was supposed to happen. I started to do my own writing back in ‘63 and ‘64 after I met John Hurt. When I was playing his music and other people’s music, he said, “Brother, I see you are a good guitar player but write you some stuff. Write some stuff for yourself. He said, “My stuff and Blind Lemon all that’s been played. Write something that nobody has ever written.” So, I started writing my own stuff.”

As part of his extensive interviews with Dr. Barry Lee Pearson, Archie Edwards explained,[8]

“It was a beautiful thing between me and John Hurt, because for the last three years of his life he’d come to my house when he wasn’t on the road, or I’d go to his house. Or we’d go to the barbershop, and we’d sit and play all night long until the sun came up. We just had ourselves a hell of a good time. When I met him, it was like I’d known him all my life. We sounded so much alike. Now John and I had several things that we were doing just alike, even though he was from Mississippi and I was from Virginia. Most people thought I was his understudy, but I was playing that way before I met him. That knocked him for a loop. He didn’t know anybody was still picking the guitar like him. I worked with John Hurt for about three years then he went back to Mississippi and passed away. I used to go down there on Rhode Island Ave. and pick him up because he lived at #30 Rhode Island Avenue, Northwest. So, if he wasn’t on the road I would call him and tell him, “John, I’ll come down and pick you up. We can go to the barbershop.” So, we would go over there and he would sit and play the guitar for my customers. Sometimes he’d have the whole barbershop full of people. We’ve had them all the way out the street, in the back and the front. I would be cutting a head of hair and if he played a song I felt he needed some backing on, I just put the tools down and pick up the guitar and follow him. So, we had a lot of fun there. Big audiences would come to hear me and John play and the people tell me about that now sometimes. “Man, I remember a time back in the sixties when you was doing big business here and John Hurt would come in here and play”… When we got together, we had some fun. We drank up many half pints. I didn’t say nothing about that. But, it’s a shame so many dead men go to the trashcan. I never heard him say a curse word and I never knew him to do anything to anybody. But he would take a drink and smoke cigarettes. That’s as far as he would go. I never knew him to speak an evil word against anybody. He was a very cool guy. So, it was an honor to meet a guy like that.”

Archie told Dr. Barry Lee Pearson, [9] “…Mississippi John Hurt asked me, he said, ‘Brother Arch, whatever you do, teach my music to other people.’ He said, ‘Don’t make no difference what color they are, teach it to them. Because I don’t want to die and you don’t want to die. Teach them my music and teach them your music.’”

That’s what Archie Edwards did and the jams at Archie’s barbershop became regular events over decades to come, and the central meeting point for the acoustic blues scene in Washington. Archie’s legacy is carried on through the local musicians who carry on traditional music. In many ways, Hurt’s wish came true. He would be gratified to know his place in music history, going strong almost eight decades after his first recording. Many burgeoning guitarists have made it a right-of-passage to learn his fingerpicking style and his originals have entered the American songbook with literally hundreds of covers recorded. He remains a cultural treasure of American folk music with global fame and a wonderful legacy as people the world over sing Louis Collins, Avalon Blues, and My Creole Belle, be it in Tokyo, Paris, London, Buenos Aires, Washington, D.C., or San Francisco. Everybody loves John Hurt and they never let him die; but the sad truth about the exploitation of his music, name and likeness lives on as a shameful indictment of the music industry.

Over the next fifty years John Hurt achieved international acclaim as one of America’s greatest and most revered folk musicians who is almost universally accepted as the most popular and successful of the “rediscovered” artists of the original blues era. He was recognized in his own lifetime, celebrated as a cultural treasure. His records are still selling and he remains a popular figure to this day. Most roots music fans would agree that the rediscovery of John Hurt was a good thing, for him and for the music world. It’s almost unimaginable to think of roots blues without him.

By all accounts, John Hurt loved performing, making music and making new friends. Many people were very kind and respectful to him. Yet, like many of his compatriots during the blues revival and “rediscovery” period, John Hurt may have found fame, recognition and artistic success, which is infinitely better than obscurity, but he never reaped the financial rewards of his newfound fame. Upon the death of Tom Hoskins from “alcohol related” causes, in response to published obituaries, Dick Waterman, an influential blues persona, writer, promoter and photographer, minced no words and spared no mercy:

“Shall I speak well of the dead?

I think not.

Tom Hoskins was scum. He was a thief and a liar. He signed John Hurt to a 50-50 contract with Hoskins taking 50%[10] of John’s earnings right off the top and John having to pay all travel, hotels, food, road and vehicle expenses and many other items out of his share. In the years of his comeback (1963-1966), John Hurt was immensely commercially successful compared to Son House, Skip James, Booker White, John Estes and any other rediscovered bluesman. Yet he returned to the South in 1966 with little money to show for his successes. At least one thing is certain: John Hurt will have his eternity in Heaven; Hoskins will go to Hell and pay for his onerous deeds.

Damning the dead with no regrets.”

Dick Waterman, Oxford, MS[11]

Considering that Hoskins’ (Fang’s) sole claim to fame in life was finding Hurt and bringing him out of obscurity, this indictment sheds a harsh light on his character and on the exploitation that many black blues artists experienced. The tongue-in-cheek term “Blues Mafia,” a loose group of mostly decent and well-intentioned people, now takes on a more sinister meaning when one looks behind the self-congratulatory hype. Ironically, and indicative of the reality of who controls the narrative and who has the power, John Hurt’s true story is barely noticeable over the tide of press information released by Hoskins over the years. Using today’s Internet searches turns up countless articles, each telling the same hyperbole that makes Hoskins out to be a hero who rescued Hurt from poverty and from obscurity. In the perpetual music business story, the question arises of who gets to speak for whom. The artist’s side is hardly told, and if so, it is the narrative his handler wanted the world to believe. Everybody loved John Hurt, but nobody knew how he felt and what he went through because he didn’t get to tell his own story other than what served the marketing objective. Admittedly, Hurt was very guarded about revealing his true feelings. He never criticized anybody, so it’s hard to know whether he was covering up or not.

Prior to his “rediscovery,” John Hurt had been living in harsh conditions, as a farm laborer and sharecropper in Mississippi in the pre-civil rights era. He was an old man who had toiled all of his life in the mean environment of pre-civil rights Jim Crow segregation and oppression. Suddenly he was catapulted to national fame, on the big stages, surrounded by people who directed and advised him, took him from concert to concert, and the old man complied and obeyed. He hardly had a choice but to trust his new handlers. All indications were that he loved playing, enjoyed the newfound fame and that he willingly participated, even that he had a pretty good time, but he was not in control. He was being controlled and manipulated and the contracts and business dealings were clearly not in his favor. Hurt was so lovable and unthreatening to the white blues establishment that they referred to him as “a kindly, gentle man who carried himself with quiet dignity.”[12] The fact is that he was an old man with a fourth-grade education who had been taken out of his own environment and was now being managed by young white guys.

Money was being made, but it mostly went to those who recorded and minded Hurt. The managers, Music Research Inc., pocketed the big money. In his biography of John Hurt, Philip Ratcliffe stated, relative to a lawsuit brought by Hoskins and Rosenthal against Vanguard Records over John Hurt’s Vanguard releases:

…The case was concluded on Nov. 10, 1975, resulting in a payment of $297,000 to Tom Hoskins in 1976. Legal costs swallowed almost a third of this, but Hoskins was left with around $214,000, of which, true to his word he handed $107,000 to Gene Rosenthal (of Adelphi Records). Hoskins quickly spent his share on a home, several cars, motorcycles, records, stereo equipment and paid income taxes. The MRI contract did not specify that John (Hurt) would receive income from successful lawsuits over his recordings and apparently none of this money, which could have made a huge difference to her quality of life in her later years, went to Jessie and family.[13]

The Hurt family stood largely empty-handed while Hoskins, the handlers who used Hurt to make themselves out to be important figures in the blues world, cashed in on the music that John Hurt had played since childhood. The plunder of John Hurt personifies Woody Guthrie’s famous lyrical line “Some rob you with a six–gun, others with a fountain pen” as they absconded with Hurt’s songbook and his legacy. Hurt culturally enriched the world with his music, but financially he enriched some in the music business, just not himself. A casual Internet search today turns up many dozens of John Hurt’s albums for sale or download – most among them albums that have been selling for the last fifty years. His image and likeness is capitalized on with original photographs of John Hurt being sold for many hundreds, even thousands, of dollars per print. Many well-known artists have covered his songs, some with big names including Bob Dylan. Yet his family and estate saw little to none of the profits and royalties, according to his granddaughter Mary Frances Hurt, the president of the John Hurt Foundation.[14] Of all the “rediscovered” artists, John Hurt was the nicest, sweetest and kindest, as often described by the blues press at the time, but in the end, he was just another shamelessly exploited black musician.

Mary Frances Hurt, the musician’s granddaughter, had harsh words for the plight of her grandfather,[15]

“John Hurt had to escape those people who exploited him. His excuse to get away, to come back home to Mississippi, was that my father, his son, was on his dying bed. He didn’t have the nerve to get away from them before. He didn’t want to do it anymore because he wasn’t making any money. He was their Negro-slave. Not even an indentured servant. They wheeled him around from place to place and he had no say-so over what was coming or going, no say over the finances or anything. They uprooted him from his life and when he died they couldn’t even buy him a headstone. My father died and then my grandfather died and there were eighteen grandchildren. We had to borrow the money to bury him. My grandmother kept saying, “We’ll take care of you when John Hurt gets paid.” But, he never got paid. Since then, over all these years everybody who came around just had total disrespect. They all just exploited us and the family got nothing.”

That stands in stark contrast to the picture created by Hurt biographer Philip R. Ratcliffe, who said,

…John (Hurt) clearly enjoyed much of his rediscovery time, playing music to appreciative and adoring audiences, making many good friends and generally enjoying life. He was never rich, but John did not desire money; and although his performing career did not generate huge amounts of money, relative to what John and his family had been used to before 1963 there was enough to make a considerable difference to their lifestyle…

However, in fairness, Ratcliffe went on to say,

While they reaped some benefits from this, after John’s death Jessie and the grandchildren suffered considerable hardship almost entirely due to negligence on the part of several people, including some of those indirectly involved. Although incompetence, rather than premeditated malice, played a large part in this neglect, it has left an inexcusable legacy of hardship to the remaining Hurt family members. [16]

It’s true by all indications that he in fact enjoyed himself, that he loved playing and that there were many great aspects to his newfound fame. Yet, it is hard to believe that John Hurt, beholden to his minders, would “not desire money” considering that he had eighteen grandchildren, sixteen of whom were still living in poverty in Avalon, Mississippi. It defies logic and common sense, and it demonstrates a pattern of white music establishment paternalism that is all too evident in the written record about John Hurt. That statement is not aimed at his aforementioned biographer Dr. Ratcliffe who has been relatively sensitive to John Hurt. It is the overall story that has been perpetrated in the music press and which prevails today, as said, in part because Hurt was never allowed to speak for himself and history is tainted by romanticized fiction. If he were here today to take issue with the often-repeated notion that his exploitation and plundering was justifiable because he was “rescued” out of his sharecropper existence and given international fame, and that others pocketed his earnings while his family received a pittance, perhaps he would echo the words of disgust of his granddaughter Mary Frances Hurt.

No matter what the business end of it was, John Hurt enjoys continued musical relevance, and his years in Washington, D.C., had a major impact on the world, and the local blues scene. His wish came true. He is one of the most beloved figures in folk blues to this day.

###

[1] As the John Hurt biographer Dr. Philip R. Ratcliffe pointed out to Frank Matheis in an email of January 5, 2017, John Hurt never felt at home in the run-down neighborhood where he was moved to. The meaning here is his connection to the African American community and especially to Archie Edwards.

[2] Waterman, Dick. “John Hurt; Patriarch Hippie.” SingOut. Feb./March 1967, 7.

[3] As the John Hurt biographer Dr. Philip R. Ratcliffe pointed out to Frank Matheis in an email of January 5, 2017: The New York recording was actually completed in December 1928.

[4] Cohn, Lawrence. “Mississippi John Hurt: The Dramatic Rediscovery of a Near-Legendary Blues Singer/Guitarist.” Down Beat Magazine, July 1964, 22 -23.

[5] Harris, Sheldon, “Mississippi John Hurt,” Blues Who’s Who (Cambridge, MA: DaCapo Paperback, 1979) 257-258.

[6] Waterman, Dick. “John Hurt; Patriarch Hippie.” SingOut. Feb./March 1967, 7.

[7] Küstner, Axel. Interview excerpts from taped conversation. Original Field Recordings. Vol.6 Living Country Blues USA. Archie Edwards. The Road is Rough and Rocky. Liner notes, pp. 2 -3.

[8] Pearson, Barry Lee., Virginia Piedmont Blues- The Lives and Art of Two Virginia Bluesmen (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, Paperback, 1990) 59-60.

[9] Pearson, Barry Lee, Virginia Piedmont Blues- The Lives and Art of Two Virginia Bluesmen (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990) 59-60.

[11] Waterman, Dick, https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/bit.listserv.blues-l/hHcE-iTkulQ

[12] Fox, John Hartley. Mississippi John Hurt –Legend. Rounder CD 1100 Liner notes.

[13] Ratcliffe, Phillip. Mississippi John Hurt- His Life, His Times, His Blues. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011) 213.

[14] Hurt, Mary Frances. Personal interview with Frank Matheis. Jan. 4, 2016.

[15] Hurt, Mary Frances. Interview with Frank Matheis on January 4, 2016.

[16] Ratcliffe, Philip. Mississippi John Hurt- His Life, His Times, His Blues (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011) 227.