This is the unedited version of the article “The Holiest Thing I Know” as published in Living Blues magazine. Issue #269. Vol. 51. #5. November 2020. By Frank Matheis

The worldly chanteuse from Montreal defines herself as a Scottish-Grendadian-Canadian. “I feel like music is pretty much the same with the human spirit in that it transcends our national borders. I am very much a mixed person. I call myself a mixed-heritage black woman, because I walk through the world and people look at me and they see black, and they might assume if I’m here that I’m African American descended from slave people who were here. My enslaved ancestors came by the Caribbean side, by Grenada.”

Nowadays the singer-songwriter, banjoist and clarinetist lives in Madison, Tennessee– just outside of Nashville. She reached relative fame in the early 2000’s as a member of the Canadian duo Po’ Girl with Trish Klein of The Be Good Tanyas. Since 2012, she has partnered with her husband JT Nero in the duo the Birds of Chicago.

Her music is an amalgam of American roots, not purely blues, but certainly inclusive of blues. She advised, “I think every modern musician certainly working within any kind of American idiom owes a big debt to the blues, whether they consider themselves a blues musician or not. I don’t classify myself in any specific genre. I think of myself more as a songwriter, and I think that I’m very, very broad in my tastes in terms of what I listen to. I am not limited as to genre. My housemate Yola would say “genre-fluid” – that’s her term for herself and I agree with that because I’m very influenced by many genres and writers, and I really think I follow my ears. I feel connected to blues. I actually first became aware that I was a writer when I was given a tape in high school from the Library of Congress archival recordings, called “Sweet Petunias, Volume 1.” It was very rare –essentially of blues women singers, and it absolutely opened my heart and mind. and I related so much to just the way of women singing their own stories and how kind of radical that was. That really touched me as a young teen”

“The clarinet is my first love as an instrument, and followed closely by the banjo. I started off on piano and guitar. I’m not a trained musician. I’m self-taught. So. I play by ear and learn things by ear. Now, painfully as an adult, I’m teaching myself to read music, because my daughter is starting on piano and drums. I love the banjo very much. The banjo has become my primary songwriting tool now. In the same way, I wouldn’t say I’m a blues musician, I would say I am not really a banjoist. But I love the banjo and it has become – it’s a conduit for me to write songs and I’m very, very grateful to it.’

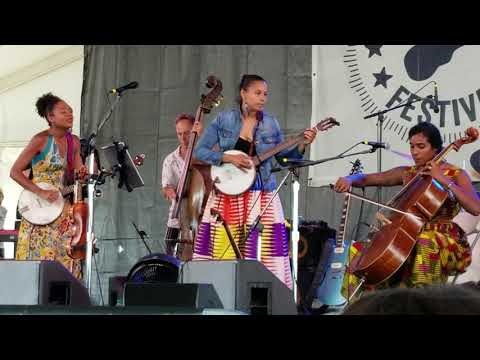

In 2019, Rhiannon Giddens asked Russell to join the all-female ensemble to record the album Songs of Our Native Daughters. She reminisced, “It came about because Rhiannon had a relationship with some of the folks at Smithsonian and had been talking to them about wanting to do an album delving into excavating and reclaiming some of the incredible compositions written by black people during the minstrel phase, which obviously is a really sensitive and difficult time because so much of that music – all that music was performed in black face by both black and white artists, because of the intensity of Jim Crow and those times. Its music that a lot of black people have left behind forever because it’s associated with so many awful negative things. But Rhiannon had a point that there’s – yes, while that is all true, these are also real artists writing real beautiful music and that there are things that are to be reclaimed and excavated and saved from that.

It began when she was on a tour of the National Museum of African American History and Culture with her daughter, and she saw a quote of a William Cowper satirical poem of the day – William Cowper was of course a great British abolitionist. A quote of his really struck her and kind of got her thinking about this idea for this project. She reached out to me and to Leyla McCalla and to Amythyst Kiah to see if we wanted to join her in this kind of – an exploration of this era of music. And we – the name – Songs of Our Native Daughters is an homage and reference to James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, which is an incredible collection of his essays, his thoughts on racism, systemic racism and black people’s place in the culture of America. I was reading some of Sojourner Truth’s work – we were discussing things before we got together. But what we ended up going for 12 days to Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, and recording – writing and recording. We ended up having so much to say to each other about all of these topics that we wrote – we just wrote most of the record. There are a couple of tunes that Rhiannon brought to the group that we excavated from that era. But what ended up happening were a bunch of original songs, many of which we co-wrote. And it just took on a life of its own, and before we knew it we started Our Native Daughters was a band. Rhiannon had invited us to be part of what she thought was a one-off project, but it just gained an organic momentum. It was just a really beautiful thing to be part of – and then still part of it. We are talking about the songs for the next record and how we’re going to do that. None of that is officially announced as of yet, but we’re talking about the next one. It’s been a really beautiful adventure to get to be a part of and with three of my favorite humans on the planet who also happen to be incredibly brilliant musicians.”

“I guess for me, playing music with people and for people is maybe the holiest thing I know of – it’s the thing that’s the closest to magic for me, other than maybe becoming a mother, which is about as holy and magical a thing as has ever happened to me. In my childhood and my teen years I was quite shy and awkward and sometimes would have trouble just speaking my feelings, but I learned that I can sing them. For me it’s very cathartic and almost therapeutic in some ways.”

“Billy Bragg was performing with our friend (and producer) Joe Henry at the Calgary Folk Music Festival. He said something that resonated with such truth “A musician’s currency isn’t music. An artist’s currency isn’t art. It’s empathy.” That’s our job as artists. That’s part of the goodness that I feel when all of those connections are happening, because you might be in a room full of people who think very differently about any number of things. You might be on stage with people who think very differently. But when we’re all sharing that language, that joy of music, that human birthright of music, it makes connections. It makes us all more human, true and at our best.”

“I am an artist who appreciates communication and collaboration above all, I suppose, and that I see that as a path towards feeling and balance in our world. When we really hear each other and we exchange true emotion with each other that are not tainted by what we think we know; or, what we assume about somebody else, when we’re really just present together, that’s where I believe feelings and balance and a restoration of all the goodness is possible in our world.”