By Frank Götz (C) 2022

There’s a new generation of players out there and they’ve come to reclaim the blues. Some are men, some women, but all are African Americans or artists of a multi-cultural heritage. What they share is a love for the music, an understanding of its history, and a deep conviction of how important Black music culture is to the world. The artists themselves won’t mention names, but even the most casual listener will hear a reaction to Trumpian politics, to the resurgence of racial violence and echoes of the Black Lives Matter-movement.

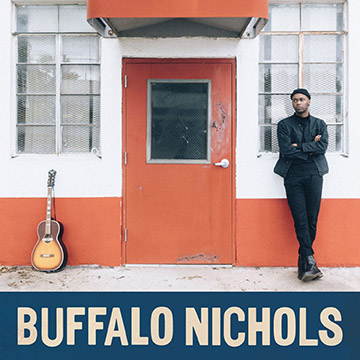

This isn’t the first blues revival, nor will it be the last. What makes the current one so exciting, however, is the return of social commentary. On one hand, we have acoustic renegades like Jontavious Willis, Jerron Paxton, Rhiannon Giddens, Allison Russell, and Valerie June, to name a few of the more powerful acts. We then have electrified ones like Shemekia Copeland, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, or Gary Clark, Jr., although you won’t find profiles for them here. And then we have some up-and-coming traditional performers that are even more outspoken – performers like Carl “Buffalo” Nichols, the aspiring young bluesman from Milwaukee. He, too, is reinventing the blues, and although his self-titled debut is only a few months old, his music is simply stunning.

Based in Austin, Texas, Nichols is the first solo blues act signed to Fat Possum Records in more than two decades. The label began in 1992 with albums for such revered artists as Furry Lewis, R.L. Burnside, and Townes Van Zandt. Nichols’ album dropped in October 2021 and makes a fine addition to their roots music catalogue. His style is quintessential folk blues – vibrato-drenched slide guitar, sparse arrangements, simple rhythms and beats – skillfully merging fingerstyle and amplified blues idioms. And the moniker? That’s in honor of his granddad, Nichols explains, who served in an all-Black infantry troop during the Korean War. The term itself was coined during the Indian Wars of 1866 and has since become a colloquial name for any African American soldier.

Featuring only eight tracks, Nichols’ album has received rave reviews while proving just how accomplished this rookie already is. One of them is a gritty cover version (Skip James), one an inspired rewrite (Vera Hall), and the rest are well-crafted originals. Hard to pick a favorite here. Most reviewers go with the album’s opener (“Lost & Lonesome”) or the socially explicit protest songs and ballads (“Living Hell”, “Another Man”, “How to Love”), but our vote goes to “These Things”, a beautiful plaintive about love and loss, regret and forgiveness. The songwriting in this tune is exceptional, and the combination of Nichols’ aching vocals, delicate picking and the bitter-sweet fiddle of Jess McIntosh make this one of the most unusual, gut-wrenching love songs in recent years.

We caught up with Nichols in San Francisco on February 11, 2022. The Buffalo Soldier of today’s acoustic blues scene has been touring relentlessly, but he was kind enough to tell us his story via Zoom. And what a story it is…

“I am a traditional blues musician when I want to be, but I’m not limited to that in any way. For me, part of getting the album out there and promoting traditional blues is reaching younger, more diverse audiences and showing them the breadth of the genre. I’d like to show people where the music comes from and how it connects to the modern world. I spent time learning traditional songs and listening to old masters, but as an artist, I don’t consider myself a blues purist. There are other influences I try to convey in my music, and some aren’t very bluesy at all…I started playing acoustic guitar when I was about 11 years old. Until that point, most of the music I heard was from MTV and FM radio. But then I started listening to the stuff in my mother’s record collection, going to record stores and scouring their CD-bins. That was when there were still CD-stores everywhere, so I would spend lots of time there, listening and learning and searching for my own tunes. Within a few months, it became an obsession. I just wanted to hear everything that had a guitar on it, and that opened my ears to all kinds of music. The first artists I could play were Chuck Berry and the Ramones. Once I figured out how to actually do their songs, I got deeper and deeper into punk rock and rock ‘n’ roll. I guess you could call that blues, too, and initially, it’s what got me on that path. My first guitar hero, though, was Jason Becker. A lot of your readers might not be aware of him, but he’s a shredder. He used to be the lead guitarist in David Lee Roth’s band, the one Roth founded after leaving Van Halen. Yeah, that was the kind of player I wanted to be as a teenager – heavy metal. Becker’s music motivated me to practice and hone my instrumental skills. Even today, I think most of what I learned on an electric guitar came from that period in my life.

The next major influences came in my college years. Like most American kids at that age, I had a folk-rock, psychedelic-kind-of singer-songwriter phase. I just loved Jimi Hendrix and James Taylor, not only for their guitar playing, but for their songwriting, too. But it wasn’t until I discovered the music of Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen that I started to take my own songwriting more seriously. Another artist I was listening to at the time was Corey Harris. He was the one that drew me back into the blues. His music made it seem like I was part of something, a big tradition worth maintaining and promoting. It felt great to see an acoustic blues player of his stature, Corey was just that good.

I met Corey Harris not too long ago. I didn’t get a chance to play with him, but we talked a bit. He was playing in Wisconsin, like a two-hour drive from where I was living. He knew about me from social media, so that was a big honor, meeting one of my idols in person. He’s someone I can reach out to every once in a while, a great resource for inspiration and all types of information regarding the blues and music in general.

I started in bands and recording music when I was 15. I was 17 the first time I actually got paid. That was really confusing. I was like, ‘No, no, that’s OK. You don’t have to give me money!’ I was happy just playing for other people. Becoming a professional was never a true decision. And I’m not sure I’d do it again if someone laid it out in front of me. By the time I turned 21, though, I had decided to do it as a living. That was when I made music a full-time thing. Then it took about another ten years before I finally got here.

I can’t remember when I first heard the blues. 13, maybe, I dunno. It must’ve been while going through my family’s music collection. My mom had some CDs that I remember well. Robert Cray’s ‘Strong Persuader’ and Jonny Lang’s ‘Lie to Me’, two big sellers in the ’80s and ’90s. The third one really changed everything for me: a big box-set called ‘Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues’ [2003]. That was when I discovered the whole story, not just the commercial stuff that was popular then. And that’s where I first heard Corey Harris. For the most part, I skipped the bluesrock thing. That was never of much interest to me. I went from contemporary blues to country blues and folk blues and never looked back

I’ve tried playing just about any kind of blues I’ve come across, but the stuff I really connect with is the heavier stuff. You know, the old stuff. The music they call Country Blues, as opposed to all the urban styles. When I hear songs by Skip James or Son House or Charlie Patton, it feels like the essence of the blues. To me, the blues is about grief and frustration. It’s not all about that, but to me, that’s where it begins.

I wrote these songs over a two-year period, with no intention of making an album. I went through about 50 or 60 I had already recorded before choosing the eight I put out. As far as songwriting goes, there’s no specific process for me. I’ve tried every method you could think of. Mostly, it’s just about being open for the inspiration. It doesn’t really matter what I do, as long as I have my guitar at hand and a pen. That’s why it’s such a difficult process, because things just have to line up. The arrangements in those songs are obviously a big part of it, and I owe a lot to the musicians who helped.”

Indeed. Be it on the road or in a studio, Buffalo Nichols is making traditional blues feel real again, a testament to the enduring influence of Black culture in America. He’s young. He’s talented. He’s connected. And the good news is, he has only just begun.