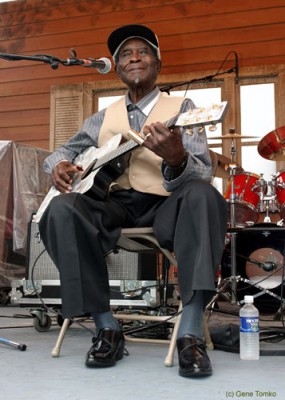

It is with great sadness that we have learned of the death of Honeyboy Edwards. He was one of the last of the originals. This listing was written before he passed away, and it will stand in his memory. The article was written when Honeyboy was still active and it should be read in that context.

It is almost unfathomable that a man in his 90’s would make the list in a directory of those who are actively contributing to the country blues today in the 21St century. David “Honeyboy” Edwards is incredible on so many levels it is truly awesome and amazing. One of the last originals from the golden era of the blues, he continues to tour, play and tell stories with an ever present sharp mind, nimble fingers and even sharper wits. While his compatriots have long since passed on, he not only keeps on rolling on but anyone who has seen him lately will attest “Honeyboy’s still got it”. He carried on the musical tradition of his father, who was also a musician.

To understand the essence of the blues of Honeyboy Edwards, the true-hearted gritty blues, you need to understand the existential reality of African Americans in the Deep South during Prohibition, the Great Depression, the migration of African Americans to the North and the post WWII civil rights period. There is no better source for this insight than the musicians who lived through it- and who lived long enough to tell about it. David “Honeyboy” Edwards, today still a traveling bluesman at age 95, is a living testament of the African American experience in 20th Century America as much as the life story of an American artist and the history of the blues as an art form.

Edwards was uneducated and poor, like most of the original blues musicians who later became legendary, romanticized and even glorified figures of popular culture. (Nevertheless, despite any idealization, most of these bluesmen deserved their hell-raising notoriety). Edwards is a man whose naturally plain-spoken vernacular is as if you were sitting with him on his back porch, an affable old man telling his colorful tales. As can be expected from a hard-living itinerant bluesman, Edward’s shows take us through a sojourn of turbulence and excitement, from his impoverished childhood in a Mississippi sharecropper’s shack to international fame.

Living he’s done plenty. Blues entertainers in the rural south during the tumultuous times of the Great Depression lived by sex, white whiskey and blues, as did Edwards. He was a plantation laborer who shared with most blues musicians the unexpected discovery that his guitar music and life as an entertainer at Saturday house parties, the notoriously violent barrelhouses, juke joints and brothels, was a means to emancipate himself from the backbreaking, low paying drudgery of field labor. Here was a way out of the economic dependency and cycle of poverty associated with sharecropping. He could make more in a weekend of earning nickels and dimes for his songs than working up a sweat all week long picking cotton. So, Edwards became a “musicianer”, as he describes his profession, and took to the road as a young teenager. He kept moving for many decades traveling throughout the South. Edwards has seen it “all” and tells tales of relentless womanizing and associated conquests by a footloose young man who enjoyed certain privileges with his status as an entertainer in these impoverished, isolated communities. Edwards had a full life as a traveling blues musician; a freight train hopping hobo; a hustler (a cheating gambler); a forced labor camp prisoner (the harsh conditions where he was interned for the mere act of vagrancy almost killed him); a levee worker during the 1927 Mississippi River flood; a husband and father. The oppressiveness of life during Edwards’ time manifested itself not only in the harsh societal racism, poverty and the exploitative economic subjugation of blacks, but in the pervasive violence within the black community itself. Not dissimilar from today’s inner cities, black life was cheap, black on black violence common and life expectancy low. Shootings, stabbings and poisoning, mostly by drunken men fighting over women or gambling money, was common and took the lives of many – including Edwards famous cohort, Robert Johnson.

He was been friend and partner to most of the classic blues legends like Charlie Patton, Big Walter Horton, Tommy McClennan, Sunnyland Slim, Robert Johnson, Son House, Big Joe Williams, and Little Walter Jacobs. He has recorded on Chess, Arc, Evidence, Savoy Jazz, Smithsonian-Folkways and Earwig—the label that has been his home since 1976. The history of the blues is the history of Honeyboy Edwards.

Though he’s been part of the blues experience during its heyday, Edwards never reached the level of success as most of his compatriots– and only now has reached the international recognition he deserved. In part this was due to his relentless traveling- he never stood still long enough for anyone to find and record him. While Muddy Waters, Little Walter and many of his other friends enjoyed the financial rewards of their success, Edwards had to wait for his payday until the 60s blues revival, when he suddenly became of interest to international white audiences. Says Edwards about the blues revival and white blues musicians: “Because they’re white, white musicians, when they play the blues, they get the benefit of our music. They get more recognition for our music than we do. But then it makes the blues more popular, too. I think a few different ways about it. But I was glad to do something with them, because if you ain’t got nothing out there, you can’t make no money…” Alas, as Edwards, the survivor and lately pragmatist, frequently says in his book: “The world don’t owe me nothing”.

Recommended starters:

Pick up any Honeyboy CD on Earwig or

Honeyboy Edwards- Mississippi Delta Bluesman – Smithsonian Folkways