A well-known blues DJ in Long Beach, California; writer for Blues Revue and one of the foremost singer/songwriters in the traditional blues genre, Dub is a gem. This artist thrills and titillates blues lovers of the acoustic genre with his well-crafted originals, and his deep roots funky style. MacLeod, a multiple W.C Handy award nominee, was once the young apprentice and guitarist for blues masters like Piedmont player Ernest Banks, George “Harmonica” Smith and Shakey Jake Harris. He is a sizzling guitarist and an exceptional songwriter whose songs have been recorded by blues giants like Albert King, Son Seals, Albert Collins, Joe Louis Walker, Coco Montoya and many others. He also backed up legends like Big Mama Thornton, Big Joe Turner, Lowell Fulson and Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson. Wherever he plays, he mesmerizes the audience with his good nature and awesome rhythmic finger style guitar and heartfelt, soulful singing.

Doug MacLeod started playing professionally in the blues clubs of St. Louis, including the east side, the black side of town, as a teenager in the 1960s. He related his entry into the blues: “I met Ernest Bank in Toano, Virginia in 1965. He was introduced to me by a guy who asked me if I wanted to meet a real bluesman who had played with Blind Lemon Jefferson. I was 19 or 20 years old. I thought I was a real blues man. I want to go meet him but I didn’t want him to teach me anything. I was so arrogant and so young and rebellious at that time in my life. I wanted to impress him and to have him walk away from me and say, ‘Man, that white boy is good.’ So, I played something for him, and he didn’t respond. My heart dropped. He said, ‘Give me that guitar, boy.’ Then, he played some bottleneck blues. My jaw literally almost fell on the floor. Well, then he looked at me with his one eye and he said, ‘Tell me something, boy, which one moved you more, yours or mine?’ I said, ‘Yours did.’ And immediately my rebellion and all of that went down. Then, he asked : ‘You want to be a blues man?’ I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ He said, ‘Never play a note you don’t believe.’ And he looked at me, and he said, ‘Can you do that, boy?’ And I said, ‘No, Sir, I can’t do that.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’re not a blues man are you?’ And I said, ‘No, Sir.’ And my heart was down. After that he and I became good friends. Still, to this day I believe he must have seen something deep inside of me. He died three years after I met him. He froze to death in a snowstorm in that little house he had one winter night. He taught me that blues was more than the uniform I was wearing or what kind of look I had or what I kind of attitude I had. Ernest was heart to heart. Once we were sitting on a corner in Norfolk, Virginia, outside a place called the ‘Folk Ghetto’ sharing a bottle of wine together right on the street corner. I told him: ‘Ernest, you know, I want to be a blues man. I really do.’ He told me ‘If you want to be a bluesman you got to write your own blues, son.’ I said to him, ‘Look, I don’t know anything about the real blues. I’ve never been to Mississippi. I don’t know about picking cotton.’ So, he looked at me with that one eye, he said, ‘You ever been lonely?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘You ever needed a woman?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘You ever needed that little rent money?’ I said, ‘Yeah, sometimes.’ He said, ‘That’s the blues, too, son. Write about that. You’ve got to write about what you know. You’ve got to be honest.’

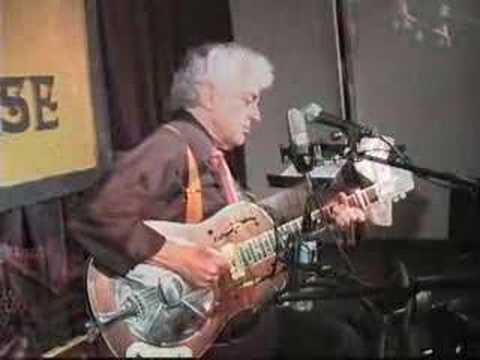

MacLeod surely took this advice to heart. As a performer and singer he is simply unmatched. He interacts with the audience with plain talk, humor and natural “we’re all neighbors and friends” dialogue. MacLeod plays a pounding, percussive heartbeat on the guitar, singing with his rich and vibrant voice. Another thing he learned from Ernest Banks is to play his metal-bodied National tri-cone resonator guitar with such rhythmic force that his audience can’t keep their feet still for wanting to dance. MacLeod remembers. “Ernest said ‘You have got to make them dance. Because he said if they weren’t dancing they weren’t drinking, and if they weren’t dancing and drinking he wasn’t going to get paid. So, you got to make them dance.’ The old bluesmen like Ernest Banks and Son House used to do that. Ernest said, ‘You ain’t shit unless you can make them dance.’ ”

He closes his shows with a standard line, “Remember, tonight you were moved by the acoustic blues,” and few would disagree. Moved, indeed!