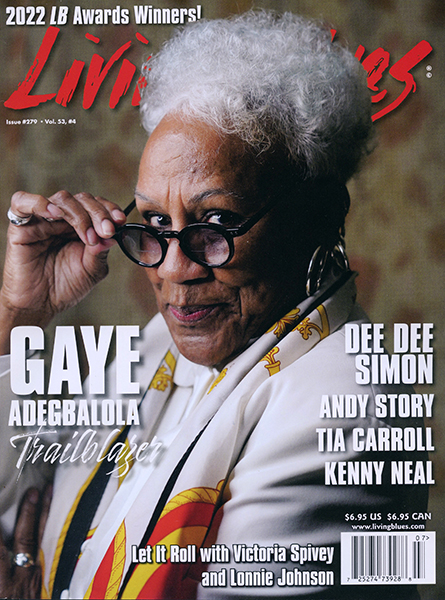

Gaye Todd Adegbalola – the Trailblazing Blues Raconteur

Author’s version by Frank Matheis. The edited version was published in Living Blues magazine #279. July 22.

Adegbalola is a modern griot who suffers no fools, summarizing her songs as, “My blues is about getting the pain out.” Many of us feel some pain nowadays, but Adegbalola’s deep blues are shaped by her dual struggles as a black lesbian and civil rights activist growing up in segregated Fredericksburg, Virginia, where she still lives today. There is nothing conventional or conservative about Gaye Todd Adegbalola. Not even just a little, and that’s a beautiful thing. She is a courageous trailblazer and hell-raiser – and damned proud of it. There is simply nobody in the blues genre like her, as the WC Handy blues award winner is idiosyncratic, most original and poignantly outspoken.

A lifetime of struggles and achievement have emancipated her spirit. Seventy-eight years old at the time of this writing, the husky voiced chanteuse is unafraid, unabashed and totally free. When a bit of bombastic artistic bluntness is needed, her defiant blues will make the point. Yet, her deep roots music is much more than a potpourri of outraged pontifications. She is as incisive, witty, humorous and sensitive as she is unbridled. Like many of the East Coast acoustic blues singers from the Piedmont region, her blues incorporates elements of folk, Appalachian and Americana music. Her unpretentious, bluntly direct lyrics and her down-to-earth folk-blues musicianship are as honest and sincere as it gets, even when mixed with a strong dose of showmanship. Her essential soul and her ability to transmit deep emotion, thoughts and feelings is quite extraordinary. Tucker Carlson will not like her one bit! This is an artist with something to say and unafraid to say it, be it in her recorded work or pandemic Facebook videos, whimsically titled “Half Lit & Talkin’ Schmack.” She maintains a rough-hewn folksy edge to her blues, a natural back-porch feeling, comfortable and accessible, while insolent and outraged.

Adegbalola may be the hippest septuagenarian on the planet. She makes even the wildest twenty-something hipsters look boring by comparison, with her trademark white hair and tattoos. Her socio-critical songs make you think and question everything. She is an activist for peace, feminism and social justice and a powerful representative of the LGBTQ community. This writer reviewed her CD The Griot in Living Blues 2019, with a line that fits today as well as then, “Gayle Adegbalola is pissed. Not just a little! She’s morally infuriated. Outright raging. She is expressing righteous indignation and outrage, and she is defiantly flipping the musical middle-finger at a long list of deserved targets.”

She initially rose to prominence as a member of the WC Handy blues award nominated trio Saffire – the Uppity Blues Women, along with Ann Rabson and Earlene Lewis (later replaced by Andra Faye). They performed together from 1984 to 2009, finding popularity among college audiences, folk festivals, women’s festivals, and the blues circuit. They were also the first acoustic ensemble signed to Chicago’s famed Alligator Records label.

Adgebalola is not only an accomplished musician and social activist but an intellectual with strong academic credentials. She graduated as her high school class valedictorian in 1961. She studied biology at Boston University and worked as technical writer and biochemical researcher at Rockefeller University. She was a bacteriologist at the Harlem Hospital in New York. In New York, she was involved in the Black Power Movement and she organized the Harlem Committee on Self-Defense. In addition, she was Virginia State Teacher of the Year in 1982.

The singer/songwriter has lived a rich life touring and recording, and she has done some exceptional things. When she went over to Paris, France, for instance, to play the Blues sur Seine concert, she also performed at the Women’s Prison in Versailles on the day when US president Obama was first elected.

Adegbalola’s social activism has made her a sought-after speaker, especially on college and university campuses, when she often lends her voice to celebrations, including Martin Luther King Day, Black History Month, Women’s History Month, and NAACP events – such as “Getting Out the Vote”, “Restoration of Rights”, and other educational programs. In 2018, the Commission for the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts invited Adgebalola to compose music to accompany an exhibit by African American painter Romare Bearden. They also had her support a film for the children’s section, “How music was created.”

She has performed at major music festivals, including:

2016 – Cognac Blues Festival, France

2017 – Heritage Music Fest, Wheeling, West Virginia

2018 – Reading Blues Festival, Reading, Pennsylvania

2021 – Blues Heaven, Denmark

During the pandemic years, Adegbalola was as active as ever. In 2019 she started her virtual performances The Front Porch: “Half Lit & Talkin’ Schmack” on social media, which then blossomed as the Covid-19 lockdowns affected the world. From 2019 to the present, she performs live on Facebook every Saturday until January of 2022. Now she is live on the last Saturday each month. Additionally, she performed or spoke virtually on numerous online activities:

2020 – Personal concerts: birthday, Mother’s Day, Juneteenth, etc.

2020 – ZamiNOBLA (Nat’l Org of Black Lesbians Association).

2021 – Shoga Films “Tain’t Nobody’s Business” concert & discussion.

2021 – Concert for OLIVIA (largest Lesbian entertainment org).

2021 – Virginia Museum Of Fine Arts – Jazz Cafe Series.

2021 – Concert for Democracy.

2021 – Pinecone Guitar Workshop.

2021 – Timbuktu to Today, Jus’ Blues Panel.

2021 – American Folklore Society Panel at Yearly Conference.

Living Blues caught up with the singer/songwriter to let her tell her own story:

“I am a mother, first. I’m a child of God. I’m very awestruck and I’m very aware of the creator in everything I do. With that in mind, I have been endowed with the responsibility of being both a mother and a good daughter. I am a teacher; I am a musician. I am a partner to my partner, and I am truly an activist. I have always been an activist ever since I remember first learning that I was, quote/unquote, at the time “colored.” So that’s basically in a few words who I am.

I have been a champion for marginalized people and I still am. I think on every CD that has ever been recorded by Saffire, or on my own individually, I have always included songs that speak to the human condition. Blues is about that which gives you trouble, and so often it’s just about trouble in love – there’s a lot of trouble. I have been a Griot all my life, and I have named myself that for decades. The term is just becoming popular over the last few years, but I’ve been that for decades and I record the history of my people. Sometimes it’s in songs, sometimes it’s in prose. Sometimes it’s in dance. So that’s what I do – I keep our history alive.I jokingly say that I probably knew I was a lesbian before I knew I was black in that I really had a crush on this girl next-door and I didn’t know what it was at the time, but that was certainly in my psyche at a very young age.

When I was downtown shopping for Christmas with my mom, I must have been four to six years old – I don’t know – I wanted to stop at the soda fountain and get a drink. I was tired. I was thirsty. And mom said, “No, we can’t go in there” and she explained it to me in delicate terms, but I knew what it was. I grew up in apartheid. We can color it and say segregation, but I grew up in apartheid. Fredericksburg, Virginia, was George Washington’s boyhood home and it was a civil war battlefield – that was what my community was steeped in. For all my formative years I was told: “You’re inferior, you’re inferior.” Back then you were just totally bullied, and this informed who we were. I knew I had to go to the colored school. I knew that my great uncle had a pickup truck and every day he would come home from working at a little garage and put a blanket in the back of the truck, and all the kids would pile in and we would get to school. Now, that is not to say I had an inferior education. The best teachers I ever had in my entire life – I’ve had a lot of teachers – have been at Walker Grant elementary and high school. I really didn’t talk to or interface with white people until I went to college.

It was during those years that I became aware of segregation. I can give you just a simple little story. The only place with air conditioning in the town was the movie theater, and on Saturdays we would go to the Colonial Theater – and of course we had to sit upstairs in the balcony. It was a break from the heat – and we would watch Hopalong Cassidy and Lash LaRue and people like that and we would get our ticket stub when we went in. They had a game where they called the number on your ticket stub – and one time my number was called. I think it was Roy Rogers. I was called to go downstairs to play on the stage in the white part of the theater. I went on stage, and it was pin the tail on the donkey, and I missed the tail by a mile, and everybody laughed. I carried that weight for the longest time, because I had the opportunity to show white folks that I was as good as they were, but I failed, and consequently I failed my people. I carried that weight for years. I mean, I guess I carried it longer than years, because I can resurrect the whole situation and the whole feeling easily – and I was a kid. I was just a kid.

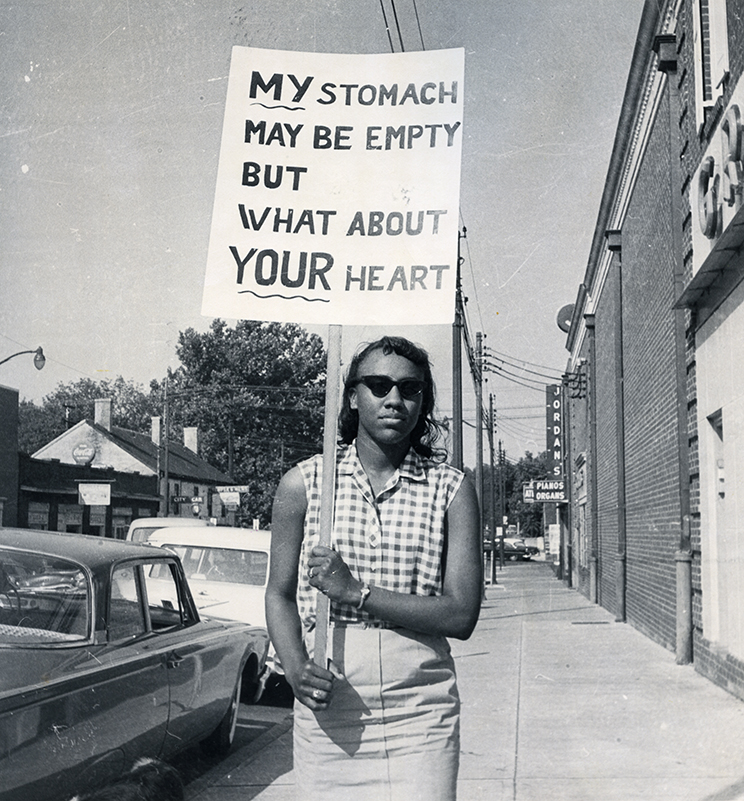

Free Lance-Star newspaper, 1960.

We also played bulldozer on the streets. I had to walk downtown to go to my school, and the whites who lived downtown had to walk uptown to go to their school, and we should just try to push each other off the sidewalk. That was what was. It doesn’t sound like much, but that was the kind of stuff I lived with as a kid. Later on, of course, there were the sit-ins, which started in Greensboro, North Carolina. That’s where the sit-ins happened, at the chain stores, like Woolworth’s, People’s Drugstore, Newbury’s and Grants – and we had the same four stores all over the South. I was part of the youth group of the NAACP here. We picketed and we boycotted, and I was in high school at this time.

No, we did not have the police dogs. No, we did not have the viciousness of Mississippi. However, we fought the same fight and we’re still fighting the same fight. I remember one night we were having a sit-in protest and the building was surrounded by white folks, and some of them were waving the Confederate flag – the same flag that was marching through the capital on January 6, 2021. Anytime we saw that flag we knew that it was a flat-out symbol of hatred. I knew that whoever had that flag hated me and I stayed away from that person. So that whole little fight [*over the Confederate flag on Kenny Wayne Sheperd’ s car] that rippled through the blues foundation earlier this year – we all know what the flag means. Issues like that have informed my songwriting. I have more than one song about the Confederate flag. I’ve written about terribly low wages. I’ve written about the lack of affordable housing, the lack of health care. Now, we are in the middle of this pandemic. In all of 2020, I did not write one song. I couldn’t. I just couldn’t.

I’m here and queer – get over it. I’m old and I’m black. I don’t get as much radio airplay play, and I don’t get booked in a lot of the different venues. I think it’s because I’m an activist. My straight out and out CD, which is Gaye Without Shame received a blues music nomination from the blues music awards and I performed it on stage. I don’t think anybody really held that against me too much. I’ve had a few people make comments to my face, and probably there were some comments behind my back – but see, I have been oppressed as a black person, as a poor person, as a woman, as a single parent, as a lesbian, and now as an old person I’m starting to get it right now. But by far the greatest oppression has been my blackness – it’s no comparison to the women issues.

Many of the women who were speaking up about women in the blues were upset because they weren’t treated well in the studio. I’m thinking about how many black women are just struggling to put food on the table. It’s a whole different fight all together – all you got to do is look at those women who work in nursing homes. It’s a sin and a shame that they have to work to get the lowest salaries for the hardest jobs. With Saffire we made those points, because Ann was such a feminist. When we formed the group, I didn’t even call myself a feminist per se. I think that’s because of the history of feminism. It goes back to when women were fighting for the right to vote, and the black women who were leaders in their community were told to walk at the end of the suffragette’s parade. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and all those white women leaders disrespected the smart, black, articulate women who could pull their own communities together. They would do nothing to fight for rights for black women. So back at that time, when women’s voices were first being heard, a lot of the leadership of the suffragette movement was racist – let’s call it what it is. Back from that time, black women didn’t really embrace the white women’s struggle, because they didn’t include us. As I grew and as I read, I was fighting for women’s rights also. I’m fighting for myself and my people, and I want freedom to do and say and be and love whoever I want. We didn’t exactly get total support from a lot of the blues audience. We were fighting the same fight against the war in Vietnam. That’s when I was very much involved with Black Power at that time. My ex-husband Olumide Adegbalola used to be the manager of the Last Poets. He helped to produce the Last Poets first two albums. That particular incarnation was in the late ‘60s, because there had been lots of changes. We sponsored the first rally against the war in Vietnam on Malcolm X’s birthday and that was with a group called the Harlem Committee for Self-Defense, and that was the group that I was a part of.

My mom and dad scraped their money together to get me piano lessons and I hated every minute of it. However, I loved music. My dad had a little jazz combo. My mom would bring all the records home from the Youth Canteen where she worked, so that I would hear the Platters and the Drifters and all of that.

I grew up dancing too. Mind you, still now, I’m a real dancer. I used to dance from the first note until the last, and I still do to the best I can. I shake it. I just love dancing. I love music and my parents loved music. Because we couldn’t attend many events in Fredericksburg, we would go to Washington, D.C. to the Carter Baron Amphitheatre each year. We would go to see Ella Fitzgerald with Oscar Peterson on piano. I loved Ella. Every summer we would go see Harry Belafonte. Every year Harry Belafonte had a different opening act, and one year he had Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and that’s when I heard my music. I heard my music! I was probably about 10 years old. From that point on, whenever they were playing blues – I found my music. I didn’t really play blues until I went to school in Boston University because I was a great black hope. I majored in biology, minored in chemistry. I was supposed to be a doctor. My junior year roommate bought a guitar. She never played it, so I learned how to play her guitar. She let me buy it from her for $150 over time over many months. I still have that little guitar. I’m looking at it right now – it’s placed in my bedroom, a Martin 000-18. I used to take it on the road until it started looking like Willie Nelson’s guitar, with holes in it. So now it’s retired. I started playing at Boston University because it was a time of great folk resurgence. At the time I would play along with Joan Baez records. Jackie Washington was one of the players there. It was a roundabout route to get back to the blues. I heard one of Dave Van Ronk records. I fell in love with Nina Simone. When I first went to New York, I would go to all-day gospel shows. I saw the Soul Stirrers. My favorite group was the Swan Silvertones. One time, I was listening to Nina Simone, when she was playing a blues tune, she whispered in the introduction, “This is Bessie, y’all.” That’s what got me to Bessie Smith. Once I got to Bessie, I found Ma Rainey. Then, I found Alberta Hunter, then Lucille Bogan, then Ida Cox, and then I found black feminists of course. These were the blues as Angela Davis wrote in the book called Blues Legacies and Black Feminism and it talks about how the only history of black working-class women of the early 20th Century is in the blues lyrics. I just really fell in love with Ma Rainey.

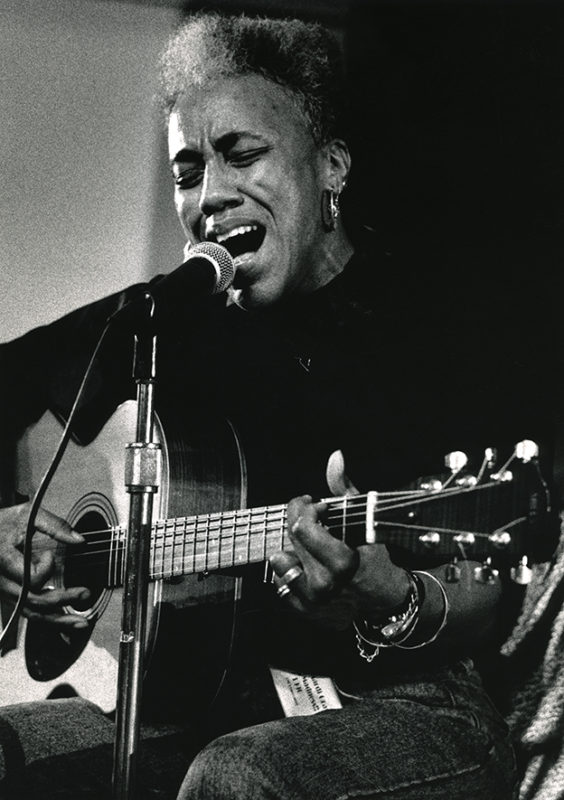

Photo by Vicky Hunt, circa mid-90s

I did a CD called Neo-Classic Blues. It was mainly blues women from the ‘20s and ‘30s. I think I had four Ma Rainey cuts on it. I had 20 cuts on there, including Alberta Hunter. I did Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom as the opening cut. I thought that Viola Davis did an excellent job in the movie about Rainey, by the way. She presented the image of what I had in my mind’s eye. I know that I am the continuation of those women.

If I were living that era, I would have been there. But now that I’m living in this era. When I do that show when I wear my white tux and white tails and a white bowtie and I strut, because they were flamboyant. You know these women were sharp.

The first thing in songwriting is the idea. I usually want the idea to be a hook. I want to come in with the substance that will inform the whole song. I have a song called Big Ovaries, Baby that was a big hit for Saffire: “I got big ovaries, baby, big enough to speak my mind.” That song started because Andra Faye had a bumper sticker on her bass case, “We Don’t Need Balls to Play.” I talk about “I’m in this game of life, I compete every day, I set my own rules – I don’t need balls to play. Offense is my defense; I won’t be caught offsides. I’m in the estrous zone and I won’t be penalized.” A new song that I just did is about John Lewis. It just knocked me over when I learned that his pastor was one of the senators elected on January the 5th from Georgia. The other senator was his former intern. So, I thought, well, damn, he ain’t dead – he ain’t dead at all. His boys are doing it for him now. I must tell people about that, because it is just so beautiful. I had been hearing the song Ain’t no grave can hold HIS body down. It’s an old Negro spiritual and I thought, ain’t no grave can hold his body down – and so I changed the lyrics to speak about what this man had done. You know, so the hook comes first.

The other song that I just wrote is called Tell Mamala. It’s a rip-off on the idea of Etta James’ Tell Mama because Kamala Harris, the vice president, her stepchildren and her nieces call her Mamala. That idea was fascinating, going from “Tell Mama” to “Tell Mamala.”

Sometimes I might struggle over a word for several days. Writing the song is relatively easy; rewriting the song is really hard, because you want every word to be good. You want every word to be important. It takes me a while to do the rewrite and then rewrite the rewrite. Sometimes, I write a love song or a breakup song. I was dealing with the ghost of a past relationship. I write to the rhythm. Then, I start putting some meat on the bones. I’m working on a song right now for civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer. I finally got the hook, which is “Fannie Lou didn’t sit like Rosa sat.”

I guess that I always just try to be honest. In many of my songs you will find humor. I’m known for my funny songs. I guess I’d say oh maybe at least 60 percent, if not more, of my songs I find humor in the pain. I’m from a family that loves to laugh, and my friends are really comical, and they inform my writing too. On the Griot there’s a song with the line “You’re Flint Water, baby — you’re dirty as you can be.” I’m talking about what happened in Flint, Michigan, but I’m putting that onto a person. “You’re toxic, baby, you’re dirty as can be – you’re dirty as Flint water.” I try to find some humor in the pain.

I try hard to be about forgiveness, and I try to live as God would have me live. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” I try, but that doesn’t mean I don’t bite. That’s why I love the Fannie Lou Hamer. That’s why I love the artist Frida Kahlo. I’ve written a couple of songs for her that I have not recorded.

Saffire was a diverse female trio comprised of what we jokingly referred to as “a Black, a Jew and a Hillbilly.” We were all united by the common bond and unified message, by our shared humanity, the way it should be in the world. We worked together for 25 years from ’84 to 2009 with just one change.

When Saffire started out, all the press we got was that we were “three old women.” Later on, oh, yeah, it’s “three old bawdy women.” Then it was, oh, “three old culturally diverse bawdy women.” And then it was like, oh, yeah, it was “three old culturally diverse bawdy women, and oh yeah, they play good music too.” With the press we had to cut through a whole lot of shit. We brought more women to the blues probably than any other act that’s ever been. We brought women to the blues. Every time we went into a club somewhere, they would go, “Where’s the band?” And we would say, “We’re the band. We’re the band.” And we did good. We opened for Ray Charles at Wolf Trap, for example. That particular concert we sold over $8000 worth of merchandize and that was in the ‘80s. Another exciting time was the first time we played at the Chicago Blues Festival and Willie Dixon joined us on stage.

In the summer of ’87, we had been playing around town for three years. John Cephas was a major impetus for us. He hooked us up with the director of the Blues Foundation Joe Savarin. John Cephas was single-handedly responsible for Saffire getting to WC Handy blues awards in Memphis the following year. I took harmonica lessons from Phil Wiggins. If you’re really going to be good at anything you really have to focus on that one thing and I’m all over the place. I write, I play, I perform and I’m the vice president of my NAACP chapter. As a matter of fact, we’re dealing with some environmental racism right now because there are tanker cars filled with chemicals in the middle of the black community. I’m on that political action committee, and we’re working on the November 2nd elections. That’s important.

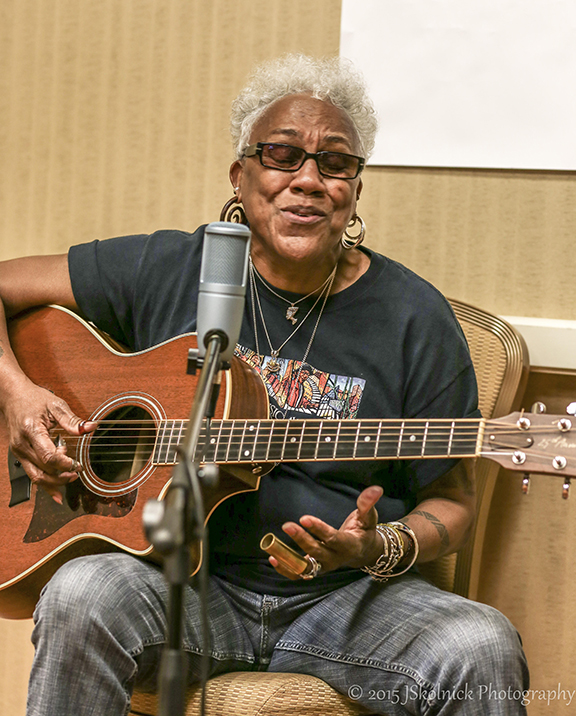

After 2009, when I was solo, I did a few tours for the State Department. In 2008, I played in Ghana and Jamaica, and Togo. In 2012 I went back to Jamaica to play at the Emancipation Park for Black History Month. In 2014 I played in Montenegro in the Balkans for Black History Mont

I did a lot of duo work with pianist Roddy Barnes. The State Department called it “Edutainment,” because I did neo-classic blues mainly and I talked about what the songs meant. I’ve had some really delightful times when I won the blues music award for Middle Aged Blues Boogie in 1990. I played in Emancipation Park in Jamaica, and there were just thousands and thousands of people there. Forthcoming, I will soon play one of the biggest blues festivals in Europe the Blues Heaven Festival in Denmark, and also the Women in Blues Fest in Riverside, Iowa. I don’t know if all my humor really came through came through between all the talk about activism, about the writing and Saffire. But I’m really a funny person.”

Adegbalola’s prime years continued after Saffire. The Virginia chanteuse is as active as ever touring, producing albums and stacking up awards and accolades. Here are just a few:

2009 – Nominated for Blues Music Award for Contemporary Blues Female Artist

2010 – Saffire nominated for Blues Music Award for Acoustic Album of the Year

2011 – Named an OUTstanding Virginian by Equality Virginia for championing GLBT equality.

2012 – Released children’s CD, “Blues in All Flavors,” on Hot Toddy Music and receives the Parents’ Choice Gold Award for Music.

2014 – 2018 formed A cappella Blues group, Gaye & The Wild Rūtz, and their CD released in 2015 – Another Blues Music Nomination.

2016 – Nominated for Blues Music Award for Contemporary Blues Female Artist

2016 to present – She serves as Vice President of the Fredericksburg, VA, Branch NAACP and works on the Political Action and the Education Committees.

2016 – Named to Pennsylvania Blues Hall of Fame

2018 – The National Women’s Music Festival presented the Kristin Lems’ “Social Change Through Music” Award to Adgebalola.

2018 – Saffire is on the cover of 25 Year Retrospective of The North Atlantic Blues Festival.

2018 – The Library of Virginia recognized Adegbaloloa as one of the 2018 Virginia Women in History Honorees (along with Barbara Kingsolver, Rita Dove and others).

2019 – The Jus’ Blues Foundation honored Adegbaloloa with the Koko Taylor “Queen of the Blues Award” for preserving traditional blues heritage.

Discography:

Picker’s Supply & Friends, Vol. II, Various Artists, 1982. Original recording of “Middle Age Blues” with Franklin Golding.

Middle Aged Blues, 1987, Saffire Records, cassette only.

Saffire – The Uppity Blues Women, 1990, Alligator Records, AL4780.

Hot Flash ,1991, Alligator Records, AL4796.

BroadCasting ,1992, Alligator Records, AL4811.

Old, New, Borrowed & Blue ,1994, Alligator Records, ALCD4826.

Cleaning House ,1996, Alligator Records, ALCD 4840.

Live & Uppity at The Barns of Wolf Trap, 1998, Alligator Records, ALCD 4856.

Ain’t Gonna Hush ,2001, Alligator Records, ALCD4880.

Saffire – The Uppity Blues Women DeLuxe Edition ,2006, Alligator Records, ALCD5613.

Havin’ the Last Word ,2009, Alligator Records, ALCD4927.

Compilations:

Essential Women in Blues, 1997, House of Blues 51416 1257 2.

Alligator Records Christmas Collection, 1992, ALCD XMAS 9201.

Genuine Houserockin’ Christmas, 2003, Alligator Records, XMASCD 9202.

Alligator Anniversary Collections: 1991, 2002,2006,2011,2016

Gaye Adgebalola released eight albums under her own Hot Toddy music label:

Neo-Classic Blues, 2004, HTMCD #1920, accompanied by Roddy Barnes on piano.

Blue Mama Black Son,2006, HTMCD #2020.

Gaye Without Shame, 2008, HTMCD #2120 — Hot Toddy Music + VizzTone. Produced by Bob Margolin.

Blues in All Flavors, 2011, HTMCD #2220.

Blues in All Flavors,2012, A children’s CD.

Is It Still Good to Ya? ,2015., Gaye & the Wild Rūtz.

The Griot, 2015.

The Freedom Song Trilogy,2022 – Volume 1.

###