“Never ever was no difference ‘tween you and I, oh.”

This article was published in Living Blues magazine – Breaking Out column. Issue # 288• Vol. 55, #1. January 2024

By Frank Matheis

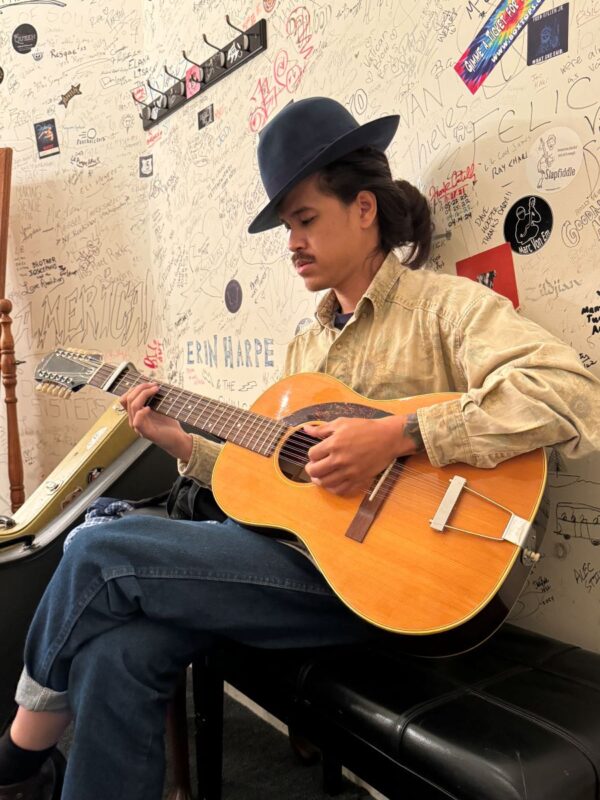

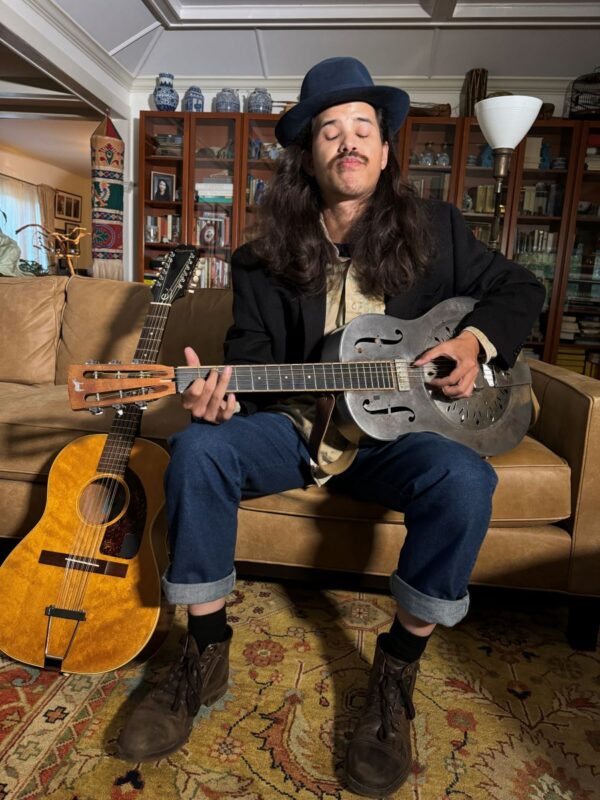

Dr. John, the late, great New Orleans king of swamp funk, was a vibrant “word inventor” who might have referred to Nat Myers as “hip tang.” That esoteric nomer fits the big-splash country-blues newcomer perfectly. It would be hard to come up with a suitable ordinary descriptive because there is nothing ordinary about the youngblood.

Myers, a good sign for creation, transcends all stereotypes and kicks out some fiery deep-roots blues bound to shake up conventions. The bluesman has received effuse critical acclaim for his debut acoustic blues album Yellow Peril. The US National Public Radio, for example, named him as one of their “Favorite Artists of 2023.” LB praised the album in the Sept. 2023 issue. The act of “breaking out” was seemingly a snap for the biracial Korean American singer/songwriter from Villa Hills in Kent County, Kentucky, noticeable by his distinct regional drawl. He also sings with distinctly Southern and black linguistic articulation. So close are his adoptions of the original 1930s deep country blues singing style that even seasoned listeners would assume him to be some long-established African American bluesman.

His debut Yellow Peril, an album packed with poetic imagery, was produced by none other than Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys, an association that has surely not hurt the marketing success of the album. Myers made several trips down to Nashville to co-write and record songs with Auerbach, famed songwriter Pat McLaughlin, and the famed Alvin Youngblood Hart. The result was a smash. By now, a case can be made that Myers is one of the new acoustic, deep-roots sensations like Jerron Paxton, Jontavious Willis, Hubbie Jenkins and Buffalo Nichols.

Myers is a superb fingerstyle guitar picker and polished singer/songwriter who has something to say. As in all good blues, he sounds ancient, if sometimes derivative, but he adds his own mark on the genre. There are a few other Asian American blues musicians, but few ascended as quickly and profoundly as Myers.

The blues has always had an element of socio-critical lyrical statements, a form of protest normally associated with the cataclysmic oppression of Black Americans in the post-slavery, Jim Crow era of segregation, exploitation, and violence.

Here we have a Korean American applying the genre to the plight of Asian Americans today, who have been blamed for the Covid pandemic and subjected to racist attacks, threatened, and harassed on the streets and subways. Sadly, many hundreds of cases have been reported since 2020, including murder. On the title track of his debut album, Yellow Peril, he laments, “Everywhere I been, somebody bein’ abused…” Unless racialism is applied, these protest blues are a most proper equivalency to that of African Americans as Myers speaks out about modern day injustices. The term “Yellow Peril” is an old racist metaphor often applied to Asian immigrants who allegedly threaten Western values, implying that they are to be feared for their alleged villainy and malevolence. Think of the Chinese Exclusion Acts of 1882 and 1924.

The artist studied poetry at the New School in New York City, where he worked odd jobs to make ends meet, a muse that is evident in his poignant lyrics. He stated, “It dawned on me that the real American epics were being told by these itinerant musicians from the ‘30s and ‘40s, even before recorded sound. That’s when I did my deep dive into the blues, so I could write my own epic.” Eventually he started busking on street corners and in subway stations, playing a few covers and a lot more originals.

He told:

“I’ve been playing since I was about 13 years old. I’m 33 now, so more than half my life I’ve been playing guitar. In terms of performing, it’s been about seven or eight years. I got started late, compared to a lot of folks. I’m a half breed. My mom was born over in Pusan, Korea, in ’52, and my dad is a typical Western European. He’s from all over the place in terms of background. I give my dad a lot of credit for showing me a wide variety of music. We used to travel a lot. He took me out West when I was real young. I remember listening to songs like Carl Martin’s old-time blues when I was young and those songs struck me real deeply at the time, but it took a long time for me to play blues as the thing that I wanted to do with music. I wanted to write poetry. I was only ever interested in learning the finger technique of country blues players. I cut my teeth up in New York City for a while. I wound up tramping a bit. I eventually started busking and I got really close with the folks up in Brooklyn’s Jalopy Theater.

Recently I’ve been able to get on the road with folks like G. Love and JJ Grey and Mofro and Willie Watson. I’m able to see where the old country blues can be taken. Until I was opening for G. this past year, I was kind of shy – I didn’t have too much to say. Recently, I have come out of my shell to be able to talk about the songs I love, being able to play my terrible takes on them. I love presenting folks like Tom McClennan, Sonny Boy or even Memphis Minnie –to people who really don’t know heads or tails about these artists who I really love – so that’s been a great privilege. I talked a little bit with Dom Flemons about how you walk the line between educating and showing people how cool country blues is. I’m an advocate for the country blues. It’s the best stuff to play. It really sets one’s mind down.

In reference to Yellow Peril, I think there are clear parallels between the turn of the 20th Century anti-immigration laws that particularly targeted the Chinese, but Asians in particular – all the way up until the ‘60s. I think a lot of the perpetuations that are going on now got the green-light when you had politicians from the top turning geopolitical facts into hateful demagoguery and using it to their political advantage. Asian folks are also entitled to the American experience without being victimized by blatant violence that has been inflicted upon them in places like New York or San Francisco… The violence and the rhetoric keep getting ratcheted up, and I think the violence is also going to trickle down. Thinking about Yellow Peril, I still contemplate how impactful a song can be or if a song can fit a solution to this larger conflict that a lot of Asian folks are going through right now, feeling a deep sense of fear that random violence can hit their own family. It makes me angry deep down.

I’m able to make a living as a musician. It feels weird to say and makes me think about Furry Lewis’s Casey Jones – “I was a natural born Eastman, I ain’t got to work”. I’ve been given a lot of chances and I just want to play country blues and get better at, because it’s all I really love playing, it’s all I really love listening to. It’s all I really care about,truth told.

I played a show over at Irving Plaza in New York City where I met a lady who was there for my performance. She spoke very earnestly and kindly with me. We had a deep discussion. She said that she thinks that a lot of people from the audience perceive me to be not half Korean and half white, but half Black and half Korean. That’s something that concerns me, because I think the racial narrative of who gets attention is complicated. I don’t want to be on the wrong side of that compass. I’m still trying to figure out a way to discuss my Asian identity in an upfront manner. I love this Black music. I love country blues music and where it comes from and the people who are doing it today. I just always want to be in the right place just in terms of where I play the music. And at the same time, I’m always going to play this music.”

Hip-tang man, indeed.