by Jody Getz

“The hardest thing about the Blues is its simplicity.” Wallace Coleman

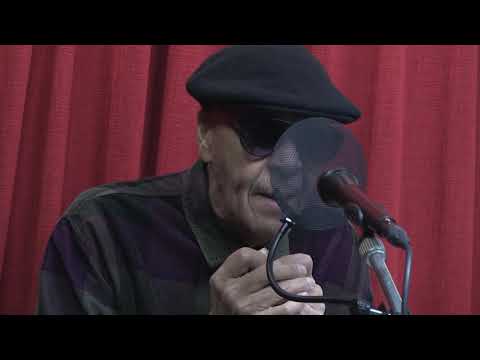

Wallace Coleman is a self-taught Traditional Blues harmonica player with a tone all his own. As a singer and songwriter who plays both diatonic and chromatic harmonicas, Wallace’s tone and feeling harken back to the electrified harmonica sounds created by 1950s era Blues giants Little Walter Jacobs and Sonny Boy Williamson II. Wallace was a young man when that sound was created, captured, and sent out into the world by way of Chicago’s premier label Chess Records. It is a sound borne of his generation but one that still resonates today with Traditional Blues musicians and fans alike. While Electric Blues is Wallace’s mainstay, he also takes great joy in performing Folk Blues, often with a more acoustic approach.

Wallace is a traditional artist who arrived to his musical path in a non-traditional way.

Born in 1936 in the Appalachian town of Morristown, Tennessee, it is a wonder that a young Wallace Coleman and the Blues ever met when they did. While much of the South was a hotbed that was teeming with the exciting Blues sounds of the times, east Tennessee was not.

Many traditional and folk artists often tell a story of being mentored in their art form and later taking on the role of artist as a way of life and means of support, but none of that was true in Wallace’s young life, growing up in an area devoid of the music he would soon discover for himself. In Wallace’s case, several events which occurred many years apart from each other charted his course and would eventually lead to a life of musical performance.

As a young boy in his small Tennessee home town, Wallace took to the harmonica, imitating the sounds of chickens in the yard and trains whistling past, and playing simple folk melodies of the day. Seeing his interest in music, Wallace’s mother, Ella Mae, saved money from her job and bought her son his own radio. One night young Wallace moved around the radio dial and landed on a Nashville station just long enough to hear The Blues. WLAC was a radio station he’d never found before that was sending out sounds he’d never heard before. Those sounds captivated him from that moment on and he would stay up late into the night listening to the WLAC disc jockeys who played the records and named the artists one Blues hour into the next. Even in school the next day Wallace says he was haunted, “I would be sittin’ in class and I could hear Howlin’ Wolf singin’ just as clear in my head.” Creating and playing guitar parts on many of those recordings was one of Chess Records’ first-call musicians, Robert Jr. Lockwood, a man who, many years later, would play an important role in Wallace’s life.

Wallace’s path changed again when as a young adult, he followed his mother and step-father’s migration from Tennessee due north to Cleveland, Ohio, in search of work. Cleveland did provide Wallace with steady work and to his delight, a bustling Blues scene that hosted touring Blues stars like Elmore James, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, and others. It was through seeing these artists perform and by listening to the records he collected, that Wallace learned the Blues and taught himself how to play the harmonica.

In the early 1960s, both Robert Jr. Lockwood and Sonny Boy Williamson II would also migrate north to relocate in Cleveland; Lockwood making Cleveland his final home; Sonny Boy staying for just several years before moving on again. Though both Lockwood and Williamson were living in Cleveland, Wallace would not meet Lockwood until much later. Wallace and Sonny Boy, however, who lived just a few blocks apart became acquainted and Wallace would often go to hear Sonny Boy perform, asking him questions about the harmonica and about his playing style. Wallace was thrilled that one of his favorite harp players, whose recordings were some of his favorites, was now an acquaintance living just blocks away and performing in Cleveland.

Meanwhile, Wallace enjoyed his position as a Work Leader with Hough Bakeries. Just like during his school days, his beloved Blues was always in his head and a harmonica was never far away. Further inspired by the touring Blues artists he’d been able to see perform live in Cleveland, Wallace would often go out to the loading docks on break to sit and play. One day a co-worker heard him and the next day brought his cousin to the bakery to meet Wallace. He was Cleveland’s Guitar Slim, a straight-ahead Alabama guitarist and singer with a standing Friday & Saturday night gig at The Cascade Lounge. That meeting sparked Wallace’s introduction to performing live and led to a year-long pairing with Guitar Slim.

Robert Lockwood said he would never hire a harmonica player…Then he heard Wallace Coleman play.

Some months into performing with the Guitar Slim band, Wallace looked up one night to see Robert Jr. Lockwood and his wife, Annie, sitting in The Cascade Lounge. When the band took a break, Lockwood crooked his index finger and summoned Wallace Coleman to his table. Before the end of that evening, this world-class guitarist who was an architect of 20th century Blues and who was now taking his own Blues around the world, offered Wallace Coleman a position in his band on the spot. Wallace had about 1 year remaining before reaching retirement and agreed to call Lockwood at that time. Soon thereafter, Wallace Coleman retired from the first career of his life and was about to embark upon his second; that of professional musician.

Robert Jr. Lockwood had taken on a day job to support his family in the 1960s when the Blues had waned for a time. When friend and Blues piano great Roosevelt Sykes called to invite him to perform at the 1970 Ann Arbor Blues Festival, Robert Lockwood never worked a day job again. By 1987 when Wallace Coleman joined Lockwood’s band at the age of 51, the Blues Circuit offered a plentiful crop of festivals and clubs in full swing that beckoned the Blues stars of the day who traveled U.S. from coast to coast to perform. Though Wallace Coleman had begun his music career decades after most of his musical peers, his talent spoke for itself. Robert discovered Wallace’s rich singing voice and pushed him out front in live performances to open the set and lead the band in several Chess-era songs, notably by Little Walter. Instead of waiting to make a headliner entrance, Robert would often play on

Wallace’s songs adding the guitar parts he had created and recorded at Chess Records some 30 years earlier.

In this Blues festival heyday, a favorite was the King Biscuit Blues Festival in Helena, Arkansas, perhaps because it brought Lockwood and so many of the Delta artists back home again. For Wallace, it was also the forging of what would become lifelong friendships with many artists he was meeting, but especially within the exclusive group of those performing, like himself, as a Blues Legend’s sideman, notably James Cotton, Calvin Jones, Willie Smith (Muddy Waters Band alumni), and Hubert Sumlin (Howlin’ Wolf Band).

Over the course of his 10 years and world travels with Lockwood, Wallace was thrilled to have shared the stage with Pinetop Perkins, Sunnyland Slim, Jimmie Rogers, Big Sam Myers, Calvin Jones, Johnny Shines, James Cotton, and Willie Smith, among others.

Wallace recorded with Lockwood on two of his releases including the 1997 Grammy-nominated “I Got To Find Me A Woman.” While Wallace could hardly imagine anything better, it seemed Mr. Lockwood was preparing him for his next life-changing event. Though some Lockwood sidemen remained with him to the end, Robert said it was clear that audiences wanted to hear more from Wallace Coleman. Lockwood began to encourage Wallace, this hand-picked, one and only harmonica player he had ever hired, to form his own band.

In 1997, Wallace Coleman indeed began the next phase of his professional music career by becoming a bandleader. The Wallace Coleman Band soon gathered momentum and was invited to perform at major Festivals and venues across the USA. Wallace also traveled to perform in France, England, Switzerland, Belgium, Spain, Brazil, and Holland. It was becoming an increasingly common practice for Festivals to incorporate Artist Workshops asking artists to perform for and interact with fans in a more intimate setting apart from their performance set and Wallace was happy to oblige. Meanwhile with the intent of recording his first CD, Wallace began to write songs. His first release entitled “Wallace Coleman” was issued by a Cleveland record label. His music received critical acclaim by the heralded Blues publications of the day.

“…One of post-war Chicago’s most indomitable torchbearers”

Blues Revue Magazine

“…Wallace Coleman should be ranked among the very best of today’s harp players”

Living Blues Magazine

Wallace formed his own label, Ella Mae Music, and to date, has issued 5 CDs to critical acclaim. Each release has included original compositions and each release has contained a mix of Electric and Folk Blues, particularly in homage to his former bandleader, “Blues in the Wind” Remembering Robert Jr. Lockwood. One release after the next has been reviewed with high praise for his harmonica tone, rich vocals, phrasing, original compositions and for the origination of Traditional Music for a genre that was beginning to slip further away from its foundation. In retrospect, like many of its original artists, the Traditional Blues genre has endured a roller coaster of conditions that were extremely challenging to its survival. In the 1960s with the creation of Motown where R&B and Soul music emerged and were topping the radio charts, Traditional Blues faded and all but disappeared.

While this American art form has often faded into the background on our own soil, typically making up less than 1% of the overall music industry presence, it has been historically embraced as a rare gem in other lands, notably the United Kingdom, where artists like Eric Clapton and John Mayall credit 1950s era American Blues artists as great inspirations for their own musical careers. Who knows if the Blues would have survived but for artists like Clapton who sought out Chester “Howlin’ Wolf” Burnett to record the album “The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions” together in the 1970s whereby American Clapton fans likely learned of their own Mr. Burnett for the first time, ironically. While the 1990’s saw the country of Japan wildly enthused about Traditional Blues and hosting huge Blues Festivals for touring American artists, that pendulum has swung; and the United Kingdom has followed suit.

“If you cut the electricity to the stage, there wouldn’t be a musician left standing”

Robert Jr. Lockwood

Unfortunately, Traditional Electric and Folk Blues have also all but disappeared from the African American musical landscape. Wallace Coleman has been referred to as a torchbearer for Traditional Blues and as such he laments the absence of faces of color in audiences and the absence of Traditional Blues in their homes and in their hands. This beautiful, simplistic and rare music created by African Americans has all but been abandoned by the same. For better or worse, the interpretation of American Blues in the hands of any other group changes many things about it, including its course in America. Wallace’s opening quote referred to the hardest thing about the Blues being its simplicity. Ironically, it is probably the simplest musical form to copy, note for note. However, he refers to the innate and powerful emotions of voice and the truthful, simplistic instrumentation of Traditional Blues that comprise its feeling. Feeling cannot be copied; it is something true that exists within and moves outward with the music, as one. Whether a haunting, stark ballad or an upbeat driving shuffle, the feeling is what resonates in the hearts of those who hear it. In the absence of feeling, much of modern Blues has arrived at a predictable, copyist template; an outwardly manufactured “feeling” comprised of heavy and protracted electric guitar-driven arrangements and affected vocals.

When something resonates in the truth, it has no need for distortion or distraction – or – “the most difficult thing about the Blues is its simplicity.” Currently, Wallace Coleman is buoyed by musicians in Brazil, Spain, and Holland who embrace American Traditional Blues and who beckon him to their countries to perform with them. These musicians revere American Blues in its purest form and are overjoyed to have a Traditional Artist of Wallace’s caliber and experience lead them, perform with them, and record with them. Especially in Brazil, young male and female artists are hungry to learn and to play American Traditional Blues and are being mentored by their elders. When Wallace tours in Brazil, he is at the heart of these activities and by sharing his music, his experiences and his history, he serves as a torchbearer for American Traditional Blues.

On other fronts, Wallace is honored to be a 20 year Hohner Harmonica Endorser. Hohner Artist profiles are reviewed for relevancy on a regular basis with the roster of Artists changing frequently. Wallace’s image has also been featured on Hohner merchandise for sales campaigns featuring harmonicas in Guitar Center Stores across the country. Wallace has been the featured performer on many radio and television programs in the USA and abroad. Though he does not consider himself to be a harmonica teacher in the traditional sense, he takes time to talk about Traditional Blues and to encourage players of all ages, at times even sending music to them from his own collection. Many harp players of all ages have credited Wallace with helping them to step onto their musical path. He has participated as a panel judge for several area Blues Society Competitions where the winners advance to compete in the Memphis Blues Challenge.

In 2013, Wallace agreed to participate in an Ohio Arts Council Traditional Arts Grant to mentor a harmonica student. This grant consisted of an ambitious number of scheduled teaching hours and various goals and activities over the course of one year. His mentee has gone on to teach harmonica to others. The City Council of Cleveland Ohio presented Wallace with a Resolution of Congratulations, naming him an Ohio Artistic Treasure. Each year, Wallace travels to his hometown of Morristown, TN, to tour with a group of hand-picked Tennessee musicians. While there he also participates in civic activities, namely Martin Luther King, Jr., events. With a long lineage of teachers in his family, he also visits local grade schools, high schools, and colleges to perform for students. In his most recent trip, a family of Mexican descent moved next door to his home place and their young son loved the harmonica and showed Wallace that he had made one out of sticks. While there, Wallace bought him a harmonica and invited him next door to show him how to begin to play some of the basic harmonica sounds. After returning home to Cleveland, he also sent the young aspiring musician some music and pictures from his own collection.

Finally, the sinking economy of the last several decades delivered significant cuts to The Arts, as sinking economies tend to do. As such, multitudes of festivals and clubs, record labels and periodicals that had been buoyed by Blues fans of the middle class have now folded. The ground on which Traditional Blues artists once stood has shifted dramatically and has now all but dissolved from underneath their feet.

All of this underscores the absolute preciousness of traditional artists like Wallace Coleman who remain true to the Traditional Blues within himself. Because the Blues is not as much something that he does but rather who he is, that essence is communicated to audiences who find themselves transported by his performances. It is not unusual for an audience member say “I didn’t know I liked the Blues until I heard you play.”

Wallace Coleman continues to perform, to travel overseas, to share, to engage and to charm his audiences, and especially to encourage up-and-coming Blues players. His love and respect for this music is present in the power of his performances. Through his innate embodiment of Traditional Blues, even seasoned musicians offer that Wallace teaches them something every time they perform with him or watch him perform.

Wallace Coleman’s love of Traditional Blues and his devotion to shepherding Traditional Blues in this 21st Century is a light that illuminates its path in the world.

6