by Frank Matheis 2021

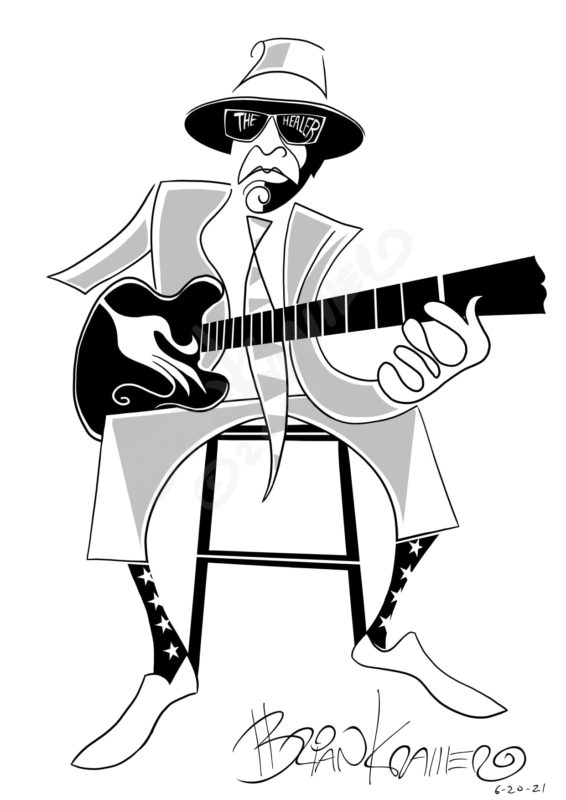

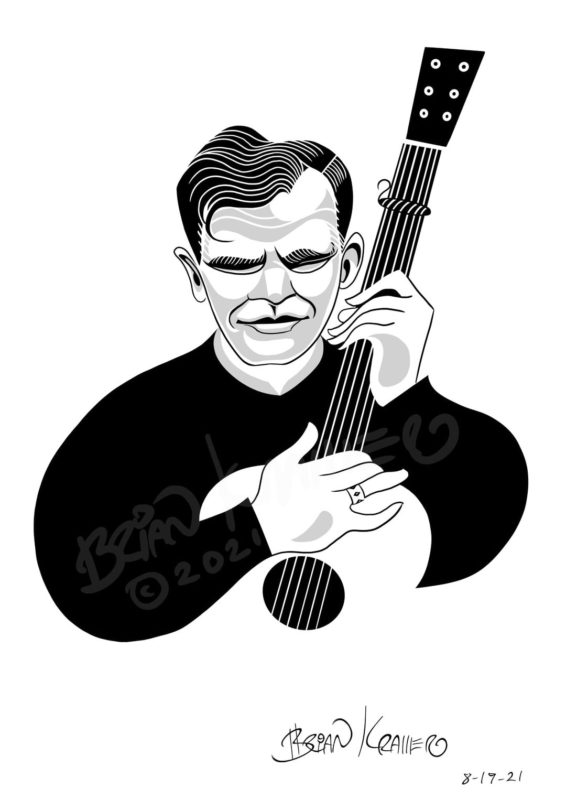

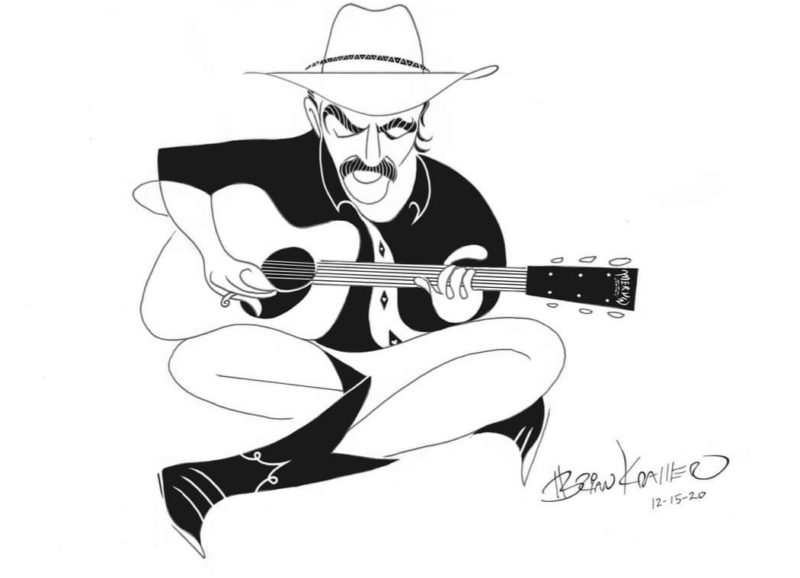

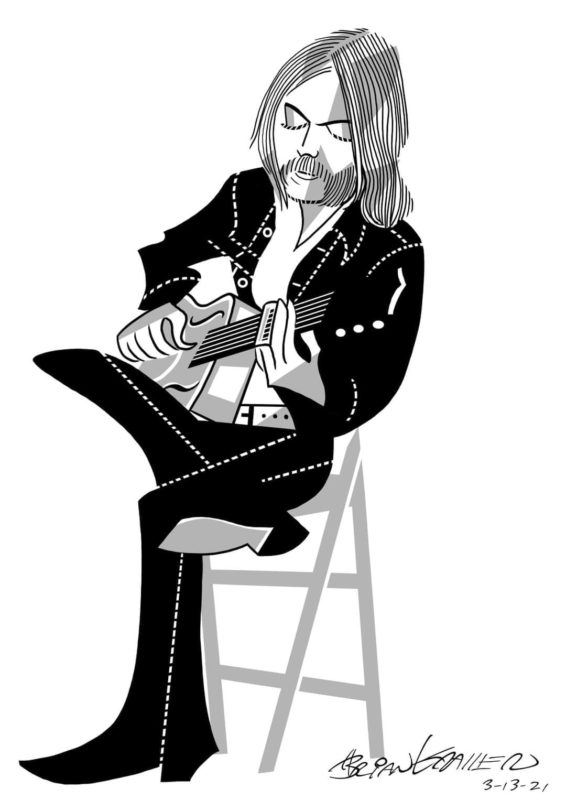

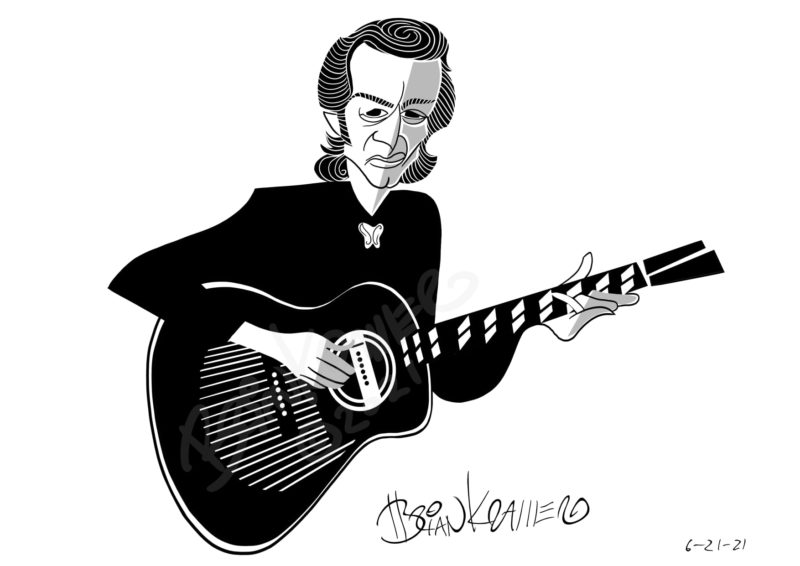

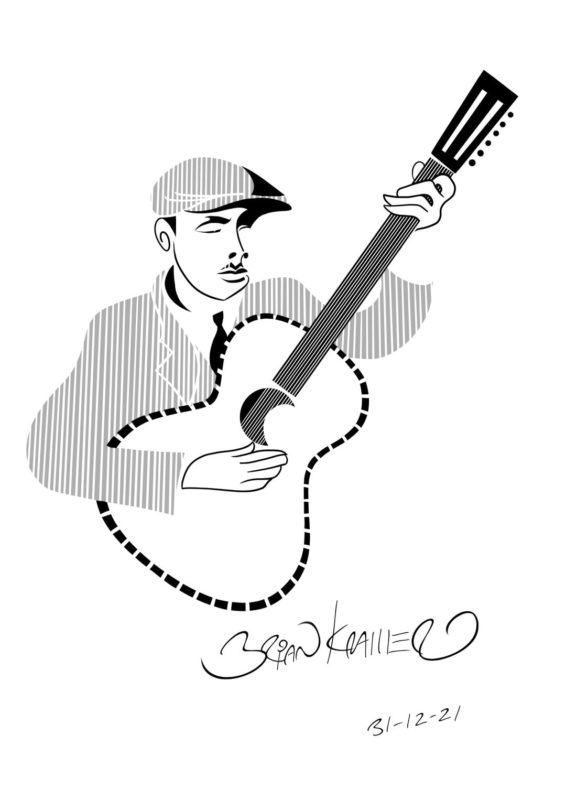

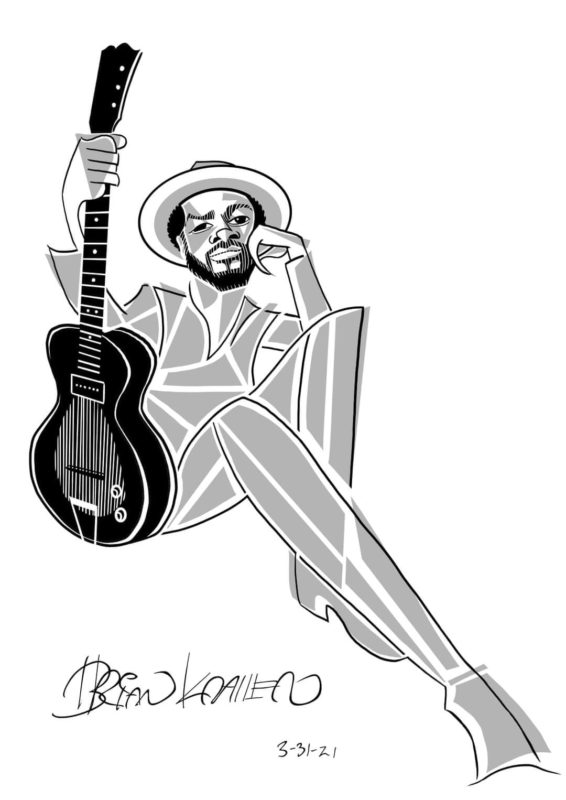

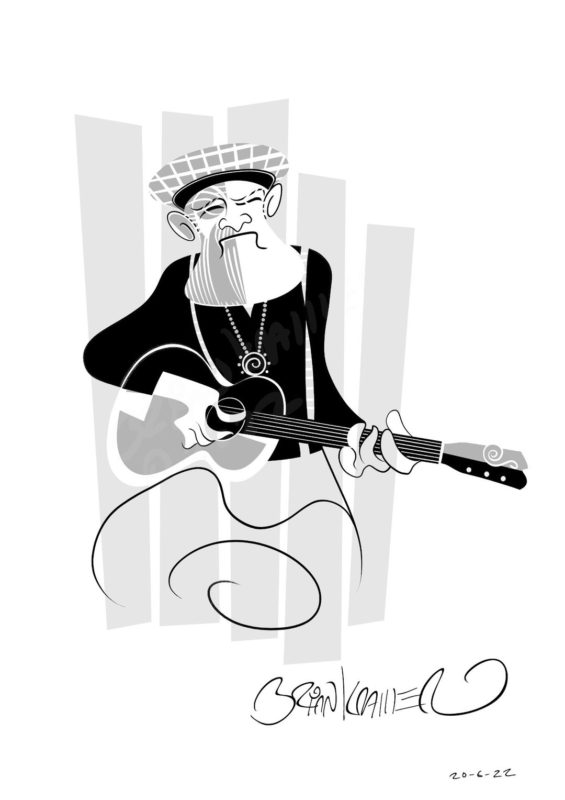

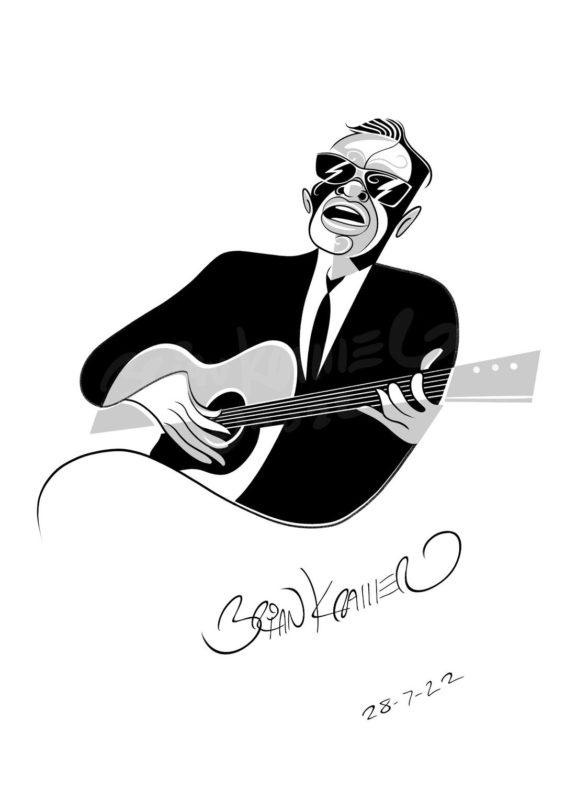

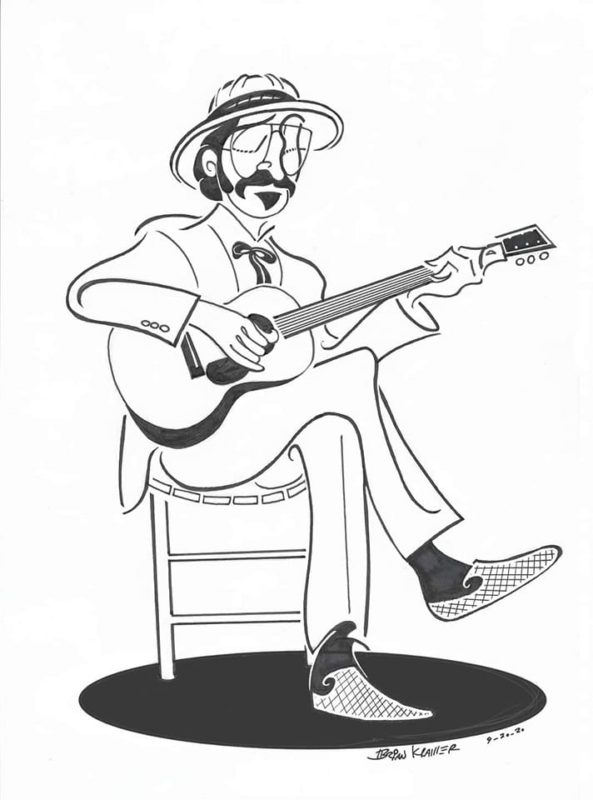

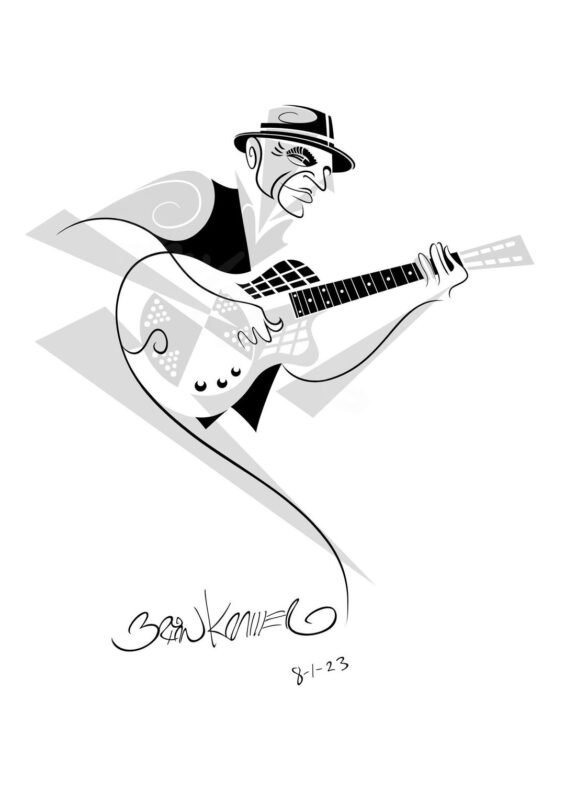

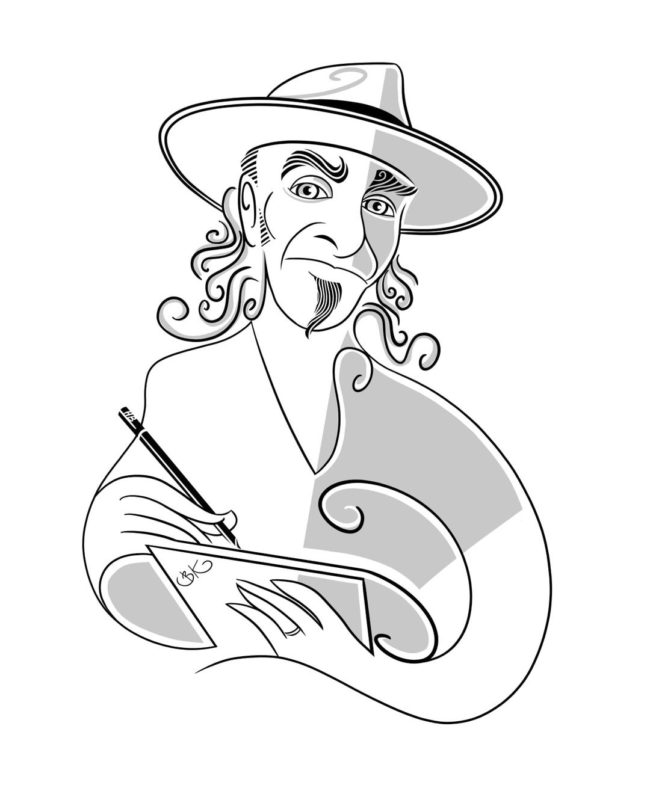

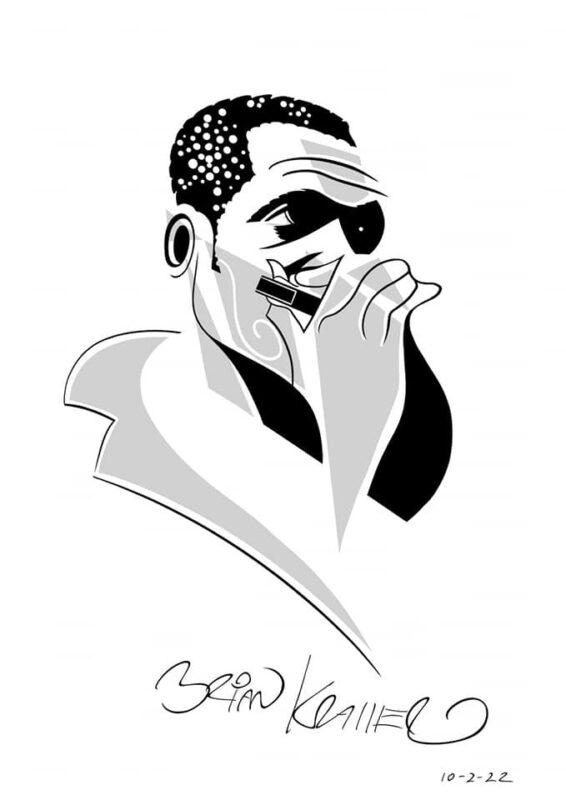

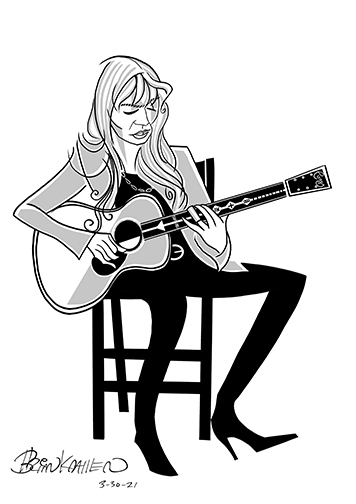

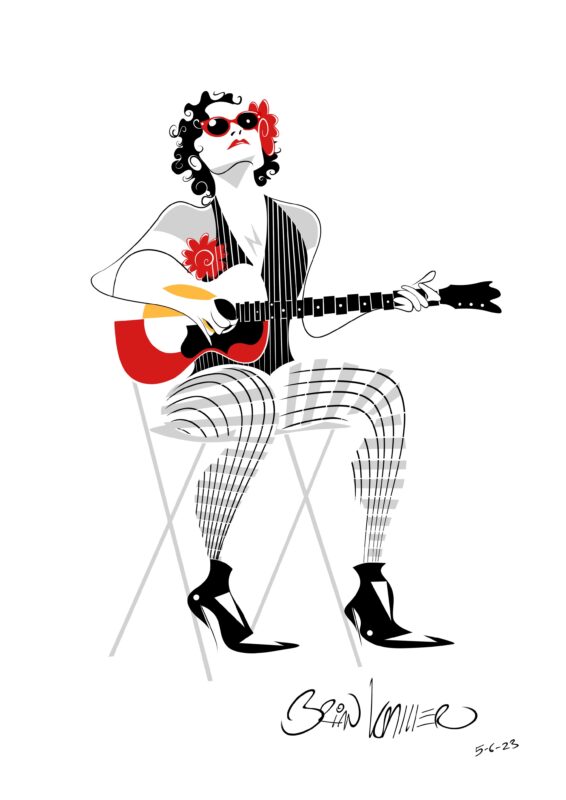

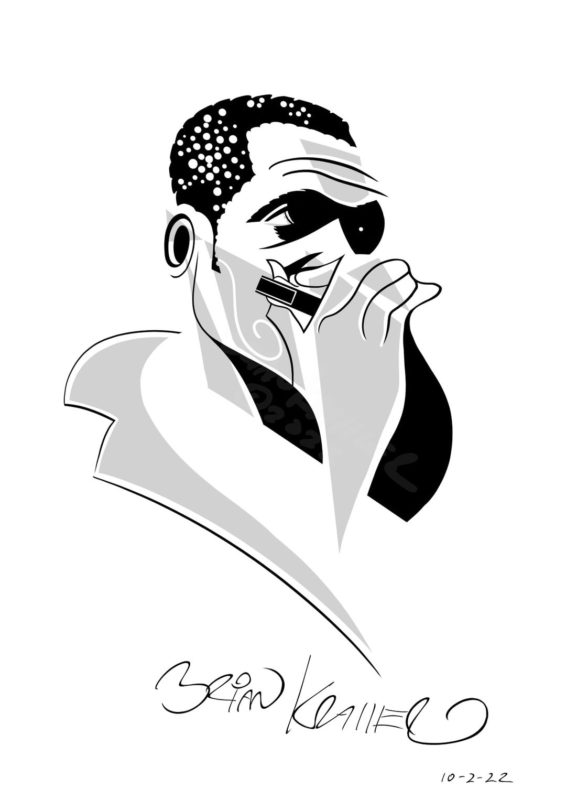

(Please note: This article contains a large number of Brian Kramer’s original caricatures. Keep scrolling all the way to the end. You’ll be amazed by how many and how good!)

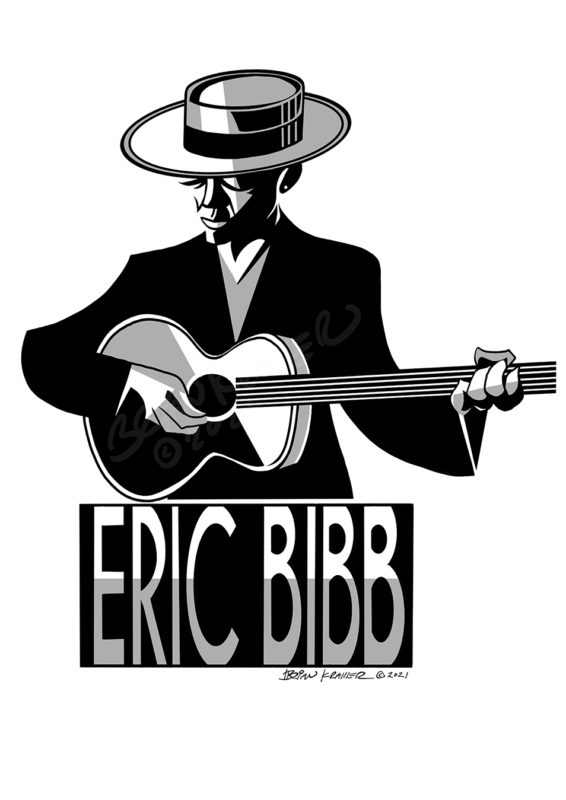

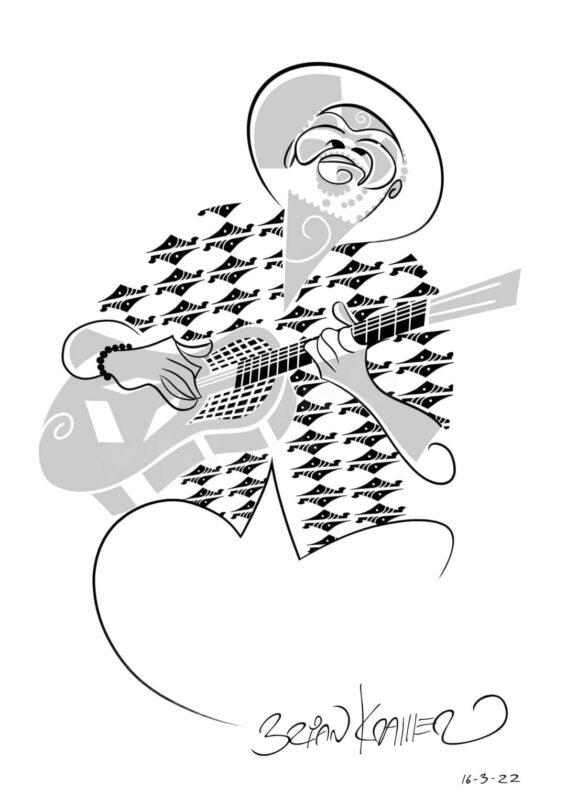

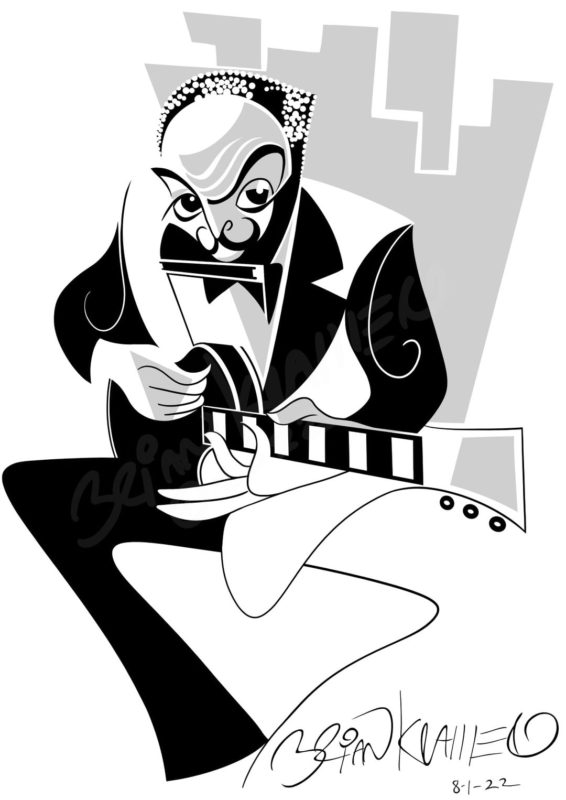

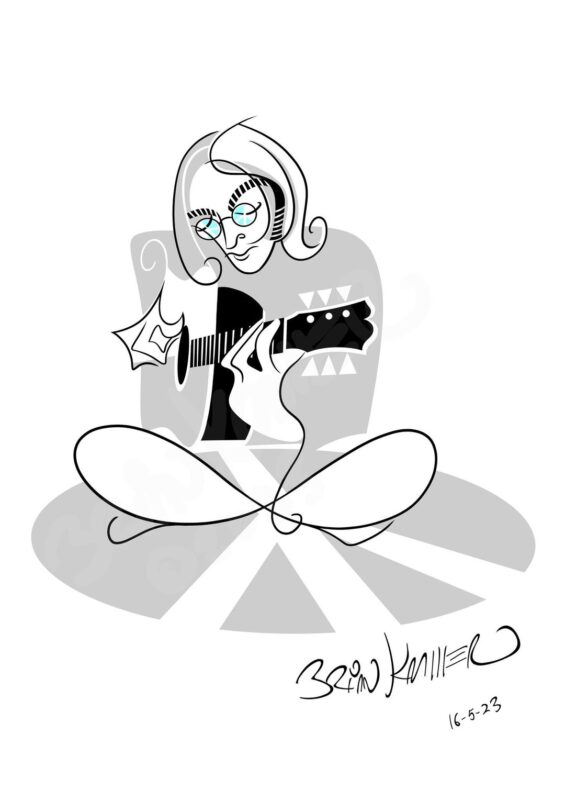

thecountryblues.com is proud and honored to feature the line drawing portfolio of acoustic blues musicians by Brian Kramer. Who better to draw blues musicians than a blues musician? All of these are for sale. If you would like to adorn your walls with these amazing portraits, let us know through the CONTACT section of this site, or look up Brian Kramer on Facebook. You can see his entire gallery in his new website, www.briankramerbluesart.com, through which you can contact him directly to purchase art.

When blues fans think of cartoonists, the iconic Robert Crumb is usually the first that comes to mind. Perhaps because he was essentially the only significant one, at least up until now. The famed underground ‘Zap Comix’ artist was a hero of the 1970s hippie era, with profound international influence on an entire generation of artists and fans. Crumb’s surreal and bizarre characters and cult-figures, like Mr. Natural, set a new style of drawing that changed cartooning. When it comes to the blues, he created a series of memorable album covers, playing cards and books. We learned from Crumb that cartoon art can make a tremendous cultural contribution to music.

Things have changed. There is a new sketcher on the block now, Brian Kramer, an American expatriate from Brooklyn living in Sweden, a serious blues musician whose life story is as interesting as his sublime drawings.

The bluesman done good

Creative people often practice more than one muse. Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Paul McCartney, Miles Davis, David Bowie, John Lennon, Fionna Apple, Ani DiFranco, John Lurie, and countless other musicians are/were also accomplished visual artists. Brian Kramer has been a professional bluesman since 1983, with his first gig at Folk City in Greenwich Village of New York. His first record back in 1989 was Brian Kramer and the Blues Masters featuring Junior Wells, Win or Lose. On these sessions the former Rolling Stone guitarist Mick Taylor also joined the iconic harmonica player Jr. Wells. Kramer toured and frequently performed with the Piedmont Blues picker Larry Johnson. He joined internationally acclaimed artist Eric Bibb on four successful tours of the US and Canada, England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Germany, Scandinavia and Japan; and he recorded several albums with him. Kramer collaborated and played on the album by Larry Johnson featuring Brian Kramer & the Couch Lizards, ‘Two Gun Green.’ Blues producer and historian Samuel Charters wrote in the album liner notes: “The group working with Larry on this album reflects some of the new realities of the blues… We’re deeply fortunate he’s here with Brian and the Couch Lizards to lay it down for us.” Brian has shared the stage, traded licks and recorded with Taj Mahal, Toumani Diabate, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Robin Ford, Bobby Rush, Corey Harris, John Mayall, Sven Zetterberg, Jimmy Dawkins and many others. He published a novel Out of the Blues and was officially inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame. A successful career all the way.

Things ain’t what they used to be

Then, a not-so-funny thing happened, just when his career was peaking. The global pandemic hit and, like musicians worldwide, Kramer was essentially unemployed since March 2020, but the Chinese have a saying. “With every loss there is a gain, and with every gain there is a loss.” The music ended and suddenly Kramer was confined at home, like billions of people worldwide. There wasn’t much money coming in. Now, with lots of time on his hands, he reverted back to a skill he had since childhood but had pushed aside in order to focus on making it as a musician. It was a reversal of a fateful choice he made as a high school student.

The Brooklyn kid on the rise

As a young teen, Brian Kramer was drawing “…to offset my nervous nature.” As a self-described “cartoonist from the get-go,” Kramer was influenced by MAD magazine, like just about every burgeoning teenage cartoonist in the mid-1970s. He also liked the line art cartoonist Gluyas Williams, Marvel and DC comic books, and the fanciful fantasy art of Frank Franzetta.

Kramer was so good as a young teen, he made it into the prestigious Mark Twain Junior High School for the Gifted and Talented on Coney Island. There he was the best of the best, a hot shot in the middle school for the visual, dramatic and musical arts. He was even mentored by Bill Kresse, the staff cartoonist for the New York Daily News at this young age. “When I was showing strong promise in Mark Twain JHS, a teacher reached out to him and he invited me to intern with him and help him create his strips and show me his process. It was a great experience. He introduced me to the famed Daily News journalist Jimmy Breslin and many other people. Bill Kresse had a very distinct way of signing his name and I adopted his “signature”, which he actually helped me develop.”

Then, he went on to the High School of Art & Design on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where the sole focus was how to become a professional artist. Kramer was a serious caricaturist interested in animation. Yet, he described the experience as “daunting”, in part because of the realistic assessment that making it as a cartoonist is about as tough as it gets. There are few professions with fewer available positions, with literally many thousands of cartoonists and only a few dozen opportunities. By this time Kramer had his doubts, and at the same time he was getting intoxicated by the blues. So, what did he do to alleviate the risk of perpetual poverty? Go to college, study finance, law or medicine? No, he quit school and made the indelible career move to become a white blues musician performing black blues. The blues had already gotten into his soul and he was possessed. He explained, “People thought I was crazy. My parents, family and friends. I was hanging up a promising career as a visual artist, a top tier caricaturist, to become a mediocre blues musician, which I was as a young teen.” After leaving school, he still took on freelance assignments, as caricaturist for Zac’s Fun House in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

A dangerous proposition

One time he was sent by his agency to a fancy party of wildly heavy opulence and decadence, thrown by a big-name New York Mafioso (whose name shall be withheld for health and safety reasons). It was the hosts’ son’s eight birthday and let’s just say that daddy pulled out all the stops on the squeezebox for his son, as very rich people tend to do. It was the mother of all kid’s parties. They even invited a caricaturist, and Kramer took the assignment. Reflecting on it today it seems like a rapturous confession of profound foolishness, but perhaps the combination of being a naïve, broke or excited teenager made him take off the thinking cap. “Wait”, you might shout, “…is he mad, drawing comics with exaggerated features that make fun of people, for Mafia kids at birthday party?” Well yeah.

Then the spoiled birthday boy threw a temper tantrum, screaming and crying and making a big scene. Just then big daddy dragged the lad over to the fateful caricaturist and gave him a glaring snarl, “If you draw my son while he is crying, I’ll kill you.” That was perhaps not a tongue-in-cheek, patronizing obfuscation. Indeed, it was an action quite frequently attributed to the famed New York mob boss. Fortunately, this sunk into our young hero. He was, after all, a Brooklyn boy and he learned quickly. “I drew him as a lovely little cherub.” Because of that fast-thinking, smoothly created winged angel, we now have a living subject to write about.

The pandemic blues

Covid 19 times hardly require an explanation. It was the same everywhere. The bloody pandemic put musicians out of business. At the time of this writing, it’s been 14-months of hardship. By the time musicians get their gigs fully back on schedule it could be nearly two years. For Kramer it was hard. His career had just peaked and then dried up completely. “I started a new album and was invited to the Swedish Grammys, playing the festivals and getting good gigs. Life was good and I was doing well.” Until he wasn’t, like so many worldwide. The decision to become a musician, decades earlier, meant that he had to focus and channel his energy toward that direction, yet he continued to practice as a caricaturist on the side. All through the years he kept it up as a sideline, but just that. He never stopped drawing, but without focus and intent he did not advance himself. He drew his own album covers and other pictures here and there, but it was all small-time stuff. Then something happened. Someone asked him to make a drawing.

The Big Bang

Like million of others, Kramer was in a pandemic induced existentialist squeeze when a fan who had seen one of his drawings asked him if he would create a special drawing on assignment. Making it as an artist had for a long time not been on his radar, but he now had the time and no other viable options. He was surprised by the sudden spark of interest in his artwork by others. That stimulus started to open that door again, and when he did, a vast explosion of new creativity was unleashed. The more he showed his work, the more acclaim he received, the more the positive reception the higher the creative energy. He rediscovered the visual side of himself, and virtually subconsciously he followed the edict every writer learns early on: “write about what you know.” Kramer had devoted his life to playing the blues, that’s what he knows, and his fans are blues fans. He let out the blues caricature illustrations one by one in a burst of creative inspiration, converging his knowledge of the music and those who played it, with total focus and discipline. He explained, “I formed a strong work ethic. I start work at six or seven every morning. In my drawings I explore the blues and I put all my experience over 40 years into my art, combining the magic of the blues through the pen, with methodical discipline and meditation. I don’t just draw the musicians. I try to put the same feeling into my work as I do in a song. I want to say the most with the least, to draw as succinctly as possible. I didn’t expect the outpouring of attention and the respect my new drawings have brought.” Every day he works eight to 12 hours. By now he has created more than 600 “pandemic era” drawings.

How does he do it?

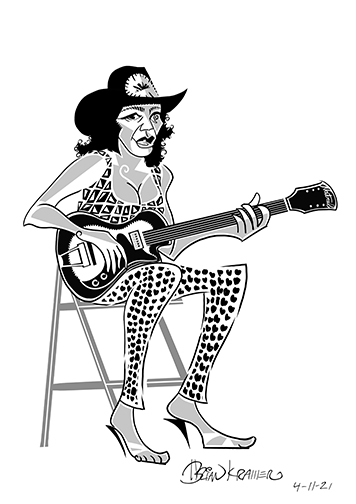

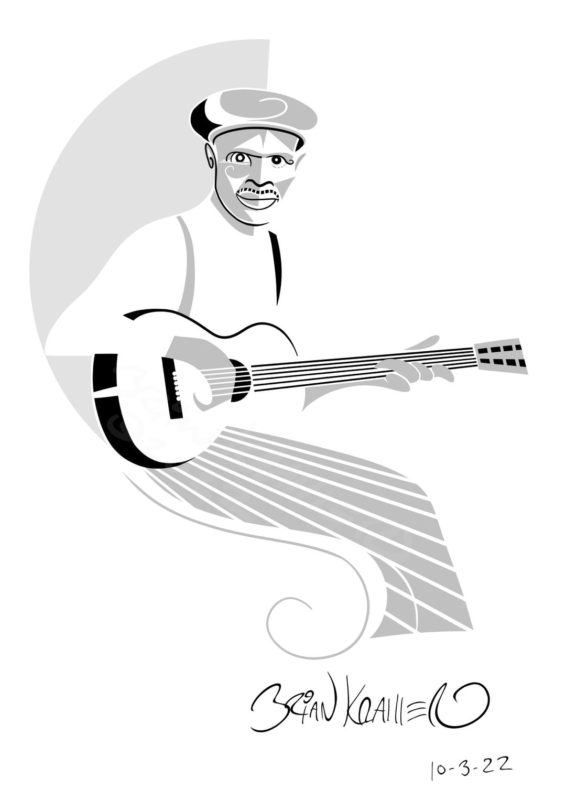

His drawings rely on strong lines to capture the moment. Like the cartoon art of the 1930s, he often uses the basic black, white and grey palate. Each piece is a delicate balance, simple, clean and elegant compositions. In some way his new work is comparable to the great New York Times and New York Herald Tribune caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, whose iconic drawings of celebrities and Broadway stars are world famous. Hirschfeld was also influenced by line art cartoonists of the 1930s, so the similarity is natural. Most notably, Kramer was evidently influenced by Hirschfeld’s stylistic, simple-line, lower torso fade-outs, when the drawing ends seemingly incomplete, into the illusion of empty infinity. Kramer may be slightly influenced by Hirschfeld, but he has his own style, both visually and in choice of subjects. If you know the music and the depicted musicians, you can literally hear the music because Kramer manages to capture the essential soul of the musician. That’s why the response among blues fans has been so overwhelming. People are surprised and amazed that suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, such a fabulous body of work should emerge. One reason for the success is that his subjects are shown respectfully. Cartoons can be harsh, even hurtful or offensive. These illustrations look like the subjects and they feel right. The response is simply “wo, cool!” People love it. Fans of the musicians especially. The blues genre has been enriched and people know it instantly.

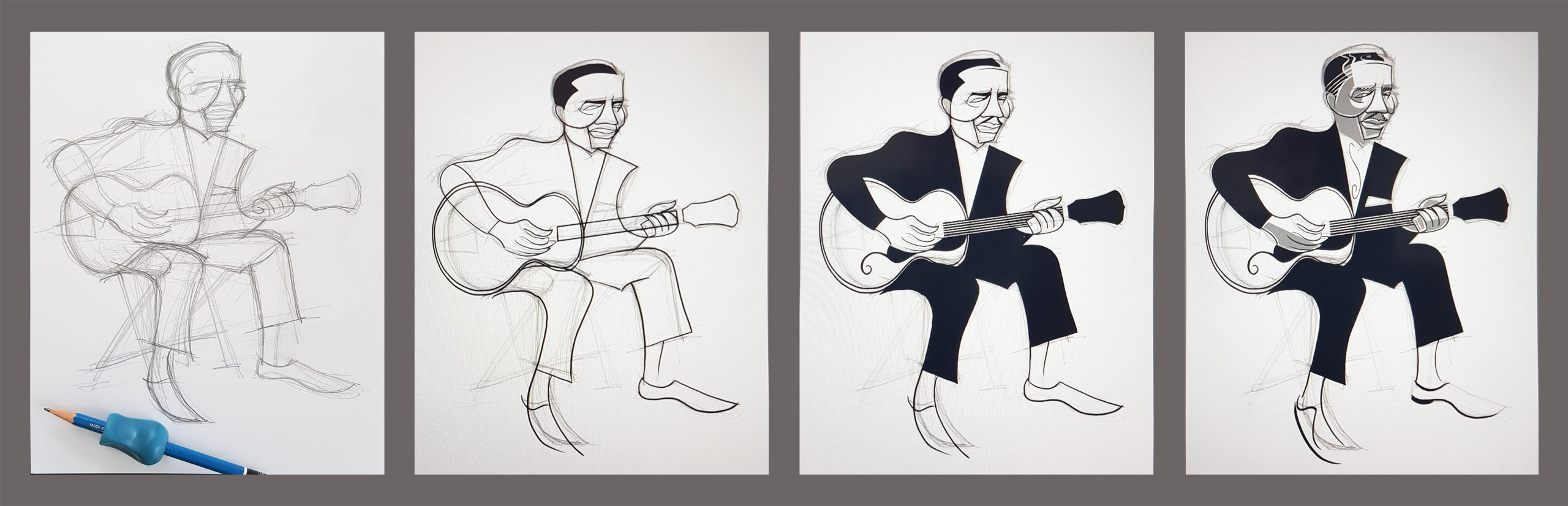

Kramer starts the process with normal sketches. He studies the character, plans the flow that captures the feeling and then methodically inks the lines. He offered this example to thecountryblues.com of the legendary blues man Muddy Waters. Bob Margolin, the former guitarist in Muddy’s Chicago band, saw the finished drawing and stated in a verified quote, “Muddy used to play guitar and sing the way you draw. Very influenced by Son House and Robert Johnson, Muddy distilled their influences, deconstructed them into a simpler presentation even when doing the same songs. Listen to Walkin’ Blues by all three. Muddy had the greatness to add his own unique voice to it. You’ve developed a signature illustrating style.”

In the course of the new blues projects, Kramer overcame his antipathy of using modern drawing tools. “I wanted to explore new methods, but I did not want to replace sketching. You can see what a drawing is “becoming something” but it is a mystery as to how or what. I start on paper, move to the tablet with stylus, but all completely done by hand, and I finalize it on paper. One of the skills I learned this past year was to navigate and master art software for professional use. Something I have avoided and was a huge weakness with an allergy to tech. Now I can format pretty much anything to spec.”

More to come

If the line had not already been taken, it would be fitting to say, “Brian Kramer’s got his groove back.” He is a musician and a fierce illustrator whose pandemic silver lining was a big bang of creative output. He burst on the scene as suddenly and unexpectedly as when Jimi Hendrix came to London to show the British how the blues is really played. His work is stunning and amazing. By now everyone knows, “Oh my God, here is the real thing!” Brian Kramer, the caricaturist is here to stay, and he is just getting started.