Editor’s Note:

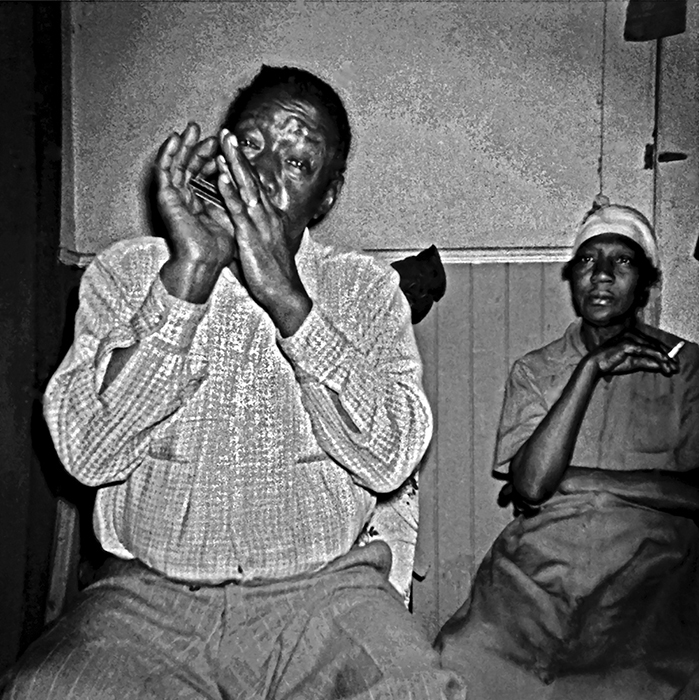

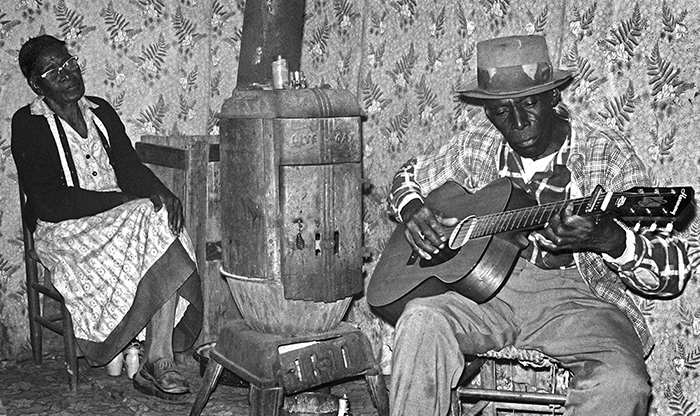

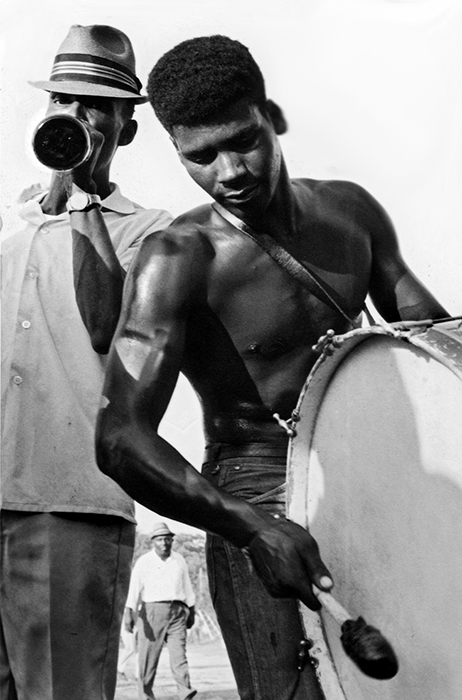

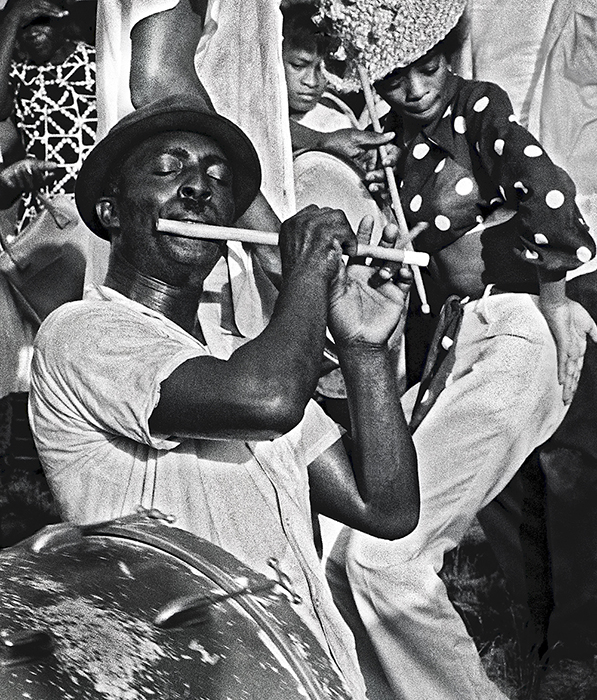

George Mitchell’s contribution to documenting blues history is immense, in part as a behind-the scenes photographer and for his field-recordings of blues musicians in their own homes. His photo-documentation shows the reality of life as it was for many of the rural Southern African American musicians. Poverty in their community was pervasive. Often they lived in segregated parts of town, in shacks, unsung and without great financial reward, even for those who later achieved relative fame. Mitchell’s photography is as much a social documentary as a music documentary. He focused on blues musicians, but he gives us a glimpse into the existentialist, socioeconomic reality of black America in the 1960s. It is particularly ironic when we leap ahead to modern day. Many of the songs that were carried on from the 1930s are still played by blues performers worldwide. Even if carried on by young black performers in 2022, their lives are so far different than the originators, who were the most oppressed, poorest and most disenfranchised members of society. We tend to forget that this way of living, segregated and impoverished, was not long ago. Indeed, relatively speaking, slavery, Jim Crow racialism and the civil rights era were relatively recent. Now, nearly 60 years after his field work, Mitchell’s photography stands as a testament to both the resilience of a people and their music. Mitchell’s work is by now a cultural treasure, a validation of traditional music culture and the immense cultural contribution of African Americans. From the humble homes of oppressed people emerged a music that is now celebrated worldwide, from the American South to Europe and as far away as Japan and Australia. Mitchell recorded the music and the blues people as they were. He shows us the reality as it was, perhaps as a counter to the marketing hype, and romanticization of the blues. The blues is, and was, the music of African Americans who lived in harsh conditions and under societal opperssion. Mitchell’s work assures that people remember their hardship.

Frank Matheis

A biography of George Mitchell –from the liner notes of the George Mitchell Collection. Fat Possum Records.

By Sam Sweet

The first bluesman George Mitchell ever met was Will Shade, the leader of the Memphis Jug Band. He and a friend from school set out for Memphis from Atlanta for their Christmas break, 1961. Mitchell’s buddy Roger Brown had an older brother who swiped a copy of Samuel Charters’ book The Country Blues, and the boys devoured it. Charters culled most of his information from players in Memphis, so George and Brown figured that’s where the blues was. Why not check it out?

They stayed with Mitchell’s aunt and went to Beale Street the next morning, asking at the drug store about local bluesmen. A guy named Whiskey motioned to follow him, and they walked to the rundown alley off Beale that was Will Shade’s address. Door opens, and there’s Will, putting out his hand and grinning. Behind him was Charlie Burse, strumming a tenor guitar on the foot of the bed. They invited the boys in and immediately started playing.

On that trip, Will Shade introduced Mitchell and his friends to Furry Lewis, Memphis Willie Boerum, Gus Canon, Bo Carter, and others. No tape recorder, no camera equipment beyond a cheap Polaroid, and no aspirations other than to hear as much of this new music as possible.

That’s how Mitchell’s career started. When you’re 17, obsession comes easy. You listen to the songs you love over and over again. You are consumed by the feeling that your favorite records are speaking directly to you. You’ll die to go to a certain concert. You are fired up by a hunger to find more and you’ll jump at anything that feeds your interest. Most people lose touch with this feeling as they get older. Not George Mitchell.

***

“You like burgers?” I am sitting with George Mitchell at The Majestic Diner on Ponce De Leon Avenue in Atlanta—Mitchell’s stomping grounds since he was a kid. The Majestic has been serving derelicts, drunks, college students and other locals since 1929. Its Art Deco interior is stained but unchanged. Mitchell is at home here; it’s his unofficial office. “It’s the most colorful joint around here, for food at least. They got good breakfast, good apple pie. Their burgers are good. I eat lunch here every day.”

The first thing you notice about him is the voice. Raised in Atlanta, Mitchell has the kind of gummy, grinning accent that can turn benign words like “plantation,” or even “hot,” into items of distinction.

Like a lot of Southerners, his speaking style is casually oratorical. In the course of a conversation, he will contract and expand his pronunciation of words and whole sentences, his voice rising and falling as the story takes it.Mitchell calls good memories “big times,” and his frequent, inimitable elocution of “fantastic” is legend among his friends…

Mitchell wasn’t the only person trolling the South for blues in the 1960s. Following the lead of Samuel Charters and John and Alan Lomax, a handful of people from Mitchell’s generation ventured into Mississippi, Tennessee, and Georgia to research blues music beginning in the 1960s. Some of them were guitarists (Henry Vestine, Bill Barth, John Fahey); some were 78 collectors (Bernie Klatzko, Pete Whelan, Dick Spottswood); some ran record labels (Peter Lowry, Chris Strachwitz); some were folklorists and musicologists (Art Rosenbaum, David Evans). All of them were obsessed with old blues, and wanted to know more…

George Mitchell isn’t a folklorist. He didn’t use a methodology when he recorded the lives and music of people in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. He didn’t have the best interview skills. He wasn’t an equipment specialist, and a lot of his recordings are rough around the edges. He’s not good with dates. And yet, Mitchell amassed a body of work that has more warmth and personality than any other field recordings from his, or any other, era.

“Field recording” is really too staid a term to ever apply to a style as outlandish and individualistic as Jimmy Lee Williams’. Williams’ music is blues only in the broadest sense; he really belongs only to his own separate genre of briar patch rock’n’roll. The electric guitar is usually associated with Mississippi émigrés, who used it to amplify their downhome styles in Chicago nightclubs, but Williams repossessed the instrument as a rural invention. He made it bark and dance, all the while hollering self-imagined hits like “What Makes Grandpa Love My Grandma So” and “Hoot Your Belly.”

Or to John Lee Ziegler, who disregarded all the rhythmic models for playing slide guitar, and instead pulled notes from his guitar like they were drops from a stream of rain falling from a roof corner. He loved to play Sam Cooke songs with a spoons player. The performances are as gentle and swift as anything by Mississippi John Hurt, but more unexpected.

Or to Houston Stackhouse, whose tugboat engine takes on Tommy Johnson songs—powered by the pickle jar and scrap heap percussion of James “Peck” Curtis—come from the same place as Captain Beefheart’s best work.

Or to the fife and drum ensembles in Como, Mississippi, and Waverly Hall, Georgia. Their music was treated by outsiders as some extraordinary remnant of early America, when its participants just treated it like party music.

Or to any of the women Mitchell recorded. Precious Bryant, Jessie Mae Hemphill, and Rosa Lee Hill could all push a song to a crawl, kneading the groove in a way that all the men missed. Mitchell was the only person to recording black female guitar players in the South in the 1960s, and the performances show that the few he found played with more presence and style than most of the half-baked bluesmen that were put on record at the time.

Or to Cecil Barfield and R.L. Burnside — by Mitchell’s estimation, the two giants among all his discoveries. The sheer strength and character in what Barfield and Burnside did makes them the equals of musical giants from jazz and rock’n’roll. Yet, their power was wholly natural and without ambition.

The people Mitchell encountered weren’t folklore demonstrations; many of them were personalities with enough weight to fill out their own record…Maybe it’s coincidence that Mitchell stumbled across so many extraordinary and utterly unique musicians. In theory, it’s possible that any of the above researchers could have come across these same people (and many did, after Mitchell). But the archive is part and parcel of who Mitchell is. He radiated warmth and eccentricity—it’s only logical that those qualities would be returned in the performances.

***

Born in Coral Cables, Florida, in 1944, and raised in Atlanta, Mitchell’s blues education was pure happenstance. He started to get into music in the 7th grade, just as Elvis was beginning to take over radio. In 8th grade, he spent the night with his school pal Roger Brown; flipping through the dial on the radio, they came upon WAOK—with WERD, Atlanta’s only black radio station. Mitchell was transfixed by the music coming through the radio. “That sounds pretty…damn…good. What is that?” The DJ said it was a record by Muddy Waters. After that, the boys started listening to WAOK and WERD a lot.

At that time, black radio was primarily rhythm and blues, with a healthy minority of blues still being played. Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Jimmy Reed, Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker: all of them had hits on black radio in the late 1950s. In his bed at night, Mitchell could pick up WEAC in Nashville, a strong signal. He’d fall asleep to the sounds of mysterious midnight DJs like Dream Girl and Alley Rat, both of whom played blues in the wee hours.

As a teenager, Mitchell was drawn to black music. As he and his friends garnered what they could about blues from Lomax’s Leadbelly LP’s, a Big Bill Broonzy album on Riverside, and Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, Mitchell was catching local blues and r&b shows. He saw Bo Diddley play a riot-inducing set at Herndon Stadium on the Morris Brown College campus. He saw Jimmy Reed and Ray Charles at the Magnolia Ballroom. He saw John Lee Hooker at Ponce De Leon Park—home of the Negro Leagues team The Atlanta Crackers—and later invited Hooker to dinner at his house (Hooker obliged and returned the favor by playing a living room set for Mitchell’s family). On one occasion, his grandmother agreed to take him to see the Staple Singers at the Municipal Auditorium, where everyone was dancing in the aisles and they were the only two white people in attendance.

After the trip to Memphis in 1961, Mitchell and his friends arranged for the musicians they’d met to come to Atlanta for a concert at Morehouse. When those plans fell through, Mitchell, Roger Brown, and Jim Lester returned to Memphis in 1962. This time, Mitchell bought a box camera, and borrowed a Norelco portable recorder from his math teacher. They had no idea what they would do with the recordings, but at least they’d be bringing back something new to listen to.

In Memphis, everything came easy. Reared in still-segregated Atlanta, the teenagers had not spent much time in the midst of any black culture. Now here they were, recording by candlelight in Will Shade’s apartment because Shade’s fuse box had blown. Everyone was drinking Golden Harvest Sherry, including the three young guests. They ended up recording Furry Lewis, Gus Canon, Will Shade, Charlie Burse, and numerous other figures who would pop in and out, like Laura Dukes and Catherine Porter.

“We had no idea why we were recording them—for posterity or something I guess,” Mitchell recalls. “It was just a big party, taking it all in.” It was summer break, 1962: the blues revival hadn’t started yet. After Lomax and Charters, they were the first people to record old-time black musicians in the South. Mitchell was a senior in high school.

***

It soon dawned on Mitchell that Memphis probably wasn’t the only place that had blues. He was in his first year at Emory when he started asking around Atlanta about old blues players. Tips from local blacks led him to guys like guitarist Willie Rockomo and harmonica player Bruce Upshaw. When the players’ homes didn’t have electricity (which was often the case), Mitchell invited them back to his house to record. Some more leads guided Mitchell to Buddy Moss, and Peg Leg Howell, whose “Low Down Rounder” (included on Charters’ The Country Blues LP) was the first 1920s blues song Mitchell had ever heard. The world around Mitchell was opening up; suddenly, the music he loved wasn’t something that existed elsewhere. It was living all around him.

After his freshman year at Emory, Mitchell pursued a job with Bob Koester’s Delmark label, which was starting to put out blues “rediscoveries.” He had hopes of becoming an A&R man for Koester, seeking out bluesman for Delmark, but his internship amounted to shipping 78s for Koester and clerking at his store, the Jazz Record Mart. While in Chicago, Mitchell collaborated with Michael Bloomfield, another young blues fanatic, on a concert series that brought the best players in Chicago to the Fickle Pickle on Monday and Tuesday nights. The shows were a success, and a soundman was brought in to tape some of theperformances. In his free time, Mitchell caught as many shows as he could: Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, Little Walter. Sonny Boy Williamson would stalk the Record Mart, buying stacks of music every week, while Big Joe Williams lived in the basement of the store. The spirit of the period is captured by Bloomfield in his book Me and Big Joe, which chronicles a nightmare road trip he and Mitchell took to St. Louis with the notoriously ornery Williams.

Mitchell eventually returned to Emory, and except for a failed attempt at locating Son House in New York City (he was actually working as a janitor in Rochester), did not do any recording for the next few years. Upon graduating, he married Cathy Celikas, an Oberlin student from Massachusetts whom he had met on an abroad trip to Luxembourg his sophomore year. In the fall of 1966, they both enrolled at the University of Minnesota, where Cathy studied social work, and George studied journalism. After their first year in Minnesota, Mitchell hatched the idea to go on a field recoding trip to Mississippi.

George Mitchell: “I figured, we’re here on the Mississippi River, let’s go down and see who we can find in Mississippi. Skip James, Bukka White, John Hurt, and Son House had all been rediscovered and recorded by that point, but no one was recording people who had not previously made records. That sounded good to Cathy. So I got in touch with David Evans, who was planning to do the same thing, and we agreed to trade leads.”

Before the trip started, Mitchell hit upon the idea that he could turn his collection of photos and recordings into a book project, after reading a review of a book of Appalachian photojournalism in a magazine in a doctor’s waiting room. He borrowed a 35 mm automatic exposure camera from the journalism department at the University, and purchased the cheapest tape recorder he could find: a Wollensack that cost him $168. “That was cheap even for back then,” Mitchell recalls. “I got lucky, because I was just going for the cheapest option, but that is the best portable recorder anybody ever made, as far as I can tell. “

There were enough blues revival labels emerging by that point that Mitchell figured if he got good material in Mississippi, he could pitch the recordings to record companies. “I considered myself a freelancer for the labels that were around then,” says Mitchell. “My plan was to record these people on spec, and if I succeeded in getting the recordings issued on a label, the artist would get paid.”

The summer of 1967 turned out to be a turning point in Mitchell’s career. He and Cathy traveled southward through Mississippi, letting tips lead them from town to town as they met and recorded established legends like Fred McDowell and Houston Stackhouse, and uncovered entirely unknown talents like R.L. Burnside and Othar Turner. Everything was done with the portable Wollensack and the small, single microphone that came with it.

Upon his return to Minnesota, Mitchell decided to turn Mississippi experiences into a master’s thesis that would double as his first book, Blow My Blues Away. He quickly found a publisher with the University of Louisiana Press.

In 1969, Mitchell finished up in Minnesota and applied for reporting jobs with several newspapers in the South. He accepted a job offer from the Columbus Ledger, in Columbus, Georgia, and moved there with Cathy. As Cathy pursued social work, and George reported for the paper, he started shooting pictures for his own stories, and getting further into the technical side of photography. They were settled in Columbus for about half a year when George suggested to Cathy one weekend that they go and check the local area for blues musicians. Jim Bunkley in Geneva, Georgia, was the first of many musicians they recorded in the area.

George Mitchell: “Now we were recording a very different sound, one that I had never heard before, and one that had never made it to record. I assume this was because Columbus was the poorest area in Georgia, and it was very isolated. It didn’t have a freeway connection, the residents didn’t travel to Atlanta, and scouts never went down there. So on weekends and some nights we’d go look for people east and south of Columbus, and we’d usually find at least one person in every town who could play at least a few songs well. Most of them did not have big repertoires. We did not find someone on the level of an R.L. during that period, but there were a lot of people who could play a few songs really well, and could do a lot of songs from this style that no one had really heard of before.”

By the early 1970s, labels like Arhoolie and Flyright had begun to release some of Mitchell’s recordings from Mississippi and Georgia, and Mitchell and the artists began to get a little bit of money back.

Mitchell: “Nobody was making a lot of money. I would always try to get the labels to advance the artist a flat rate when I recorded them, because I didn’t trust royalties. You didn’t know what was going to happen. It was a situation where a small number of records would sell, but there was a hardcore group who would always buy these blues records.”

Mitchell worked at the Ledger, and later, at the Columbus News, the city’s black newspaper, before he and Cathy relocated to Atlanta. George worked for two years at Traveler’s Aid, an agency that provided assistance to runaways, homeless, and other at-risk Atlanta residents.

In 1976, Mitchell was offered a job by the Bureau of Cultural Affairs in Atlanta to oversee the Georgia Grassroots Music Festival. The bureau gave Mitchell a budget to find and document folk musicians native to the state, and to hire people to do field research around Atlanta. From 1976 to 1979, Mitchell curated the Festival, and recorded several musicians he found in central and southern Georgia, including people such as Precious Bryant, James Davis, and John Lee Ziegler, and a few from Atlanta, such as Willie Guy Rainey. It was during his tenure with the Festival that Mitchell began his relationship with Cecil Barfield, whom he would go on to record several times over the coming years, and with whom Mitchell formed a profound bond.

From 1979 to 1981, Mitchell left the Bureau of Cultural Affairs to work for the Columbus Museum, where curator Fred Fussell hired him to do research for a project entitled “The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley.” Over these years, Mitchell and Fussell worked closely with artists from this region, which encompasses the Chattahoochee River as it runs the southern border between Georgia and Alabama to the state line of Florida. Over the years, Mitchell and Fussell uncovered the details of a regional sound that had not yet been documented on record. Among the exponents of this regional style were J.W. Warren, Jimmy Lee and Eddie Harris, Albert Macon and Robert Thomas, and Lonzie Thomas.

Following his work in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley, Mitchell made the decision to “retire” from field recording.

George Mitchell: “It had gotten to the point where I’d be out on the road for a month, ten hours a day, six days a week, before I’d find somebody. There just weren’t as many musicians as there used to be. Things had gone downhill for blues in the rural communities. You couldn’t make money doing it, and the prestige involved with being a musician in these small communities had faded. Usually the people you would find would be really good, because all the casual musicians—the people who did a couple songs really well—had given it up. But a lot of the good musicians were dying, or were too old to play well.”

As his “going out act,” Mitchell designed the National Downhome Blues Festival, which was held in Atlanta in 1984. Staged at the Moonshadow Saloon on Ponce De Leon, the three-day festival was the largest gathering of old time blues musicians ever assembled, before or since. Taj Mahal was the only revivalist musician who played, and by Mitchell’s estimation, “he sounded damn good.” The club was packed for all three days, and yielded a one-hour television program on PBS, and four LP’s on Southland. With the festival, Mitchell bid goodbye to his career in the field “in grand style.”

While it may have been odd for Mitchell to “retire” from a career that, for the most part, he still refers to as his hobby, it’s not hard to understand the change that the musical culture of the South went through between the 1960s and the 1980s. Since his teenage years, George had harbored an obsession with blues that he had never had trouble feeding. Even though Mitchell’s hunger never abated, the supply did, and when his hobby became more trouble than it was worth, he had to drop it completely.

When he gave up field recording, Mitchell devoted himself to a new passion: teaching photography.

He has spent the last twenty years working with high school students in Atlanta, first at the Communications Magnet Program at Grady High School in Atlanta, then at the Paideia School, a charter school located on Ponce De Leon. Mitchell has helped his students produce full-scale photography books such as Sweet Auburn: The Many Faces of Atlanta’s Most Historic Avenue. His photography classes have gained some renown in the Atlanta area, where he is better known for his work in the classroom than for his recordings.

In addition to his work teaching photography, Mitchell has stayed busy producing book projects of his own. Works like I’m Somebody Important: Young Black Voices From Rural Georgia (1973) and Yessir, I’ve Been Here a Long Time: The Faces and Words of Americans Who Have Lived a Century (1975) have nothing to do with the blues directly, but everything to do with how Mitchell approached his recordings. Mitchell is good with details, not data. He can’t remember what songs Peg Leg Howell played for him, but can describe vividly feeling the stumps of Howell’s severed legs against his own as they sat together in the front seat of a pickup.

For the last twenty years, Mitchell’s ongoing project has been Ronda, which chronicles the life story of a junkie street prostitute in Atlanta. It’s the kind of project that only Mitchell could get right.

***

Some of the people Mitchell first recorded—R.L. Burnside, Othar Turner, and Jessie Mae Hemphill among them—went on to become big names in their own right, while many of the extraordinary musicians Mitchell found—Jimmy Lee Williams, John Lee Ziegler, James Davis—were only heard by way of stray cuts on European LPs. Many more were never heard from again at all: everything that is known of players like Robert Longstreet and James Shorter is the brief segments that Mitchell put to tape.

A detailed picture of 20th century black musical culture in the rural South emerges from the recurring themes of Mitchell’s archive: kids learning instruments from their relatives or family friends; musicians spending their entire life within the distance of one or two towns; musicians forming irreplaceable and lifelong musical partnerships; people staging non-church-related concerts and parties for themselves in the woods and fields near their homes.

What Mitchell amassed over his 20 years in the field is as good a picture of that world as any of us are ever going to get. His recordings from Alabama and Georgia give us virtually the only picture we’re ever going to get of those areas. As Mitchell laments, “too many people went to Mississippi.” The rambling, hypnotic songs of Jimmy Lee and Eddie Harris, for instance—who George recorded in Phenix City, Alabama, in the early 1980s—offer a hint of the kinds of powerful and unique styles that must have been active in a state that went almost entirely unexplored…

George Mitchell never met McTell, but as a teenager he often ate at The Pig’n’Whistle. The drive-in was located on Ponce De Leon, a few blocks from where George and Cathy have lived for the past thirty years. He grew up in the area, and can recall with relish every fleabag motel, drive-in, liquor store, local business, and strip club that’s ever been located on the street. In the 1980s, George even published a book culled from thousands of photos he had taken of the avenue.

These days Mitchell eats lunch every day at the Majestic, Atlanta’s oldest remaining greasy spoon, but had he been around in 1940, George would have probably been at the Pig’n’Whistle with Lomax. Not as a hard-nosed canvasser, but as a patron, absorbing the sights and sounds of his avenue and scarfing burgers. Or maybe taking one of his classes of young Atlantans there, showing them how to photograph the world around them.

Among his many “firsts,” Mitchell was the first to treat undiscovered, unrecorded musicians in the South with the same interest and attention that others had given Skip James, Son House, and John Hurt. The players in Mitchell’s archive are too extraordinary to be contained by a curator’s catalogue. There is too much presence on these recordings for them to be relics. The culture was always old, weird, and American, sure, but never distant. Not to George Mitchell.

Sam Sweet

Maine via Mississippi

May 2007

Thanks to George and Cathy Mitchell, Jake Fussell, and Fred Fussell for making these notes possible.

Reproduced with permission from the author / Copyright © 2022 Sam Sweet, All rights reserved.”